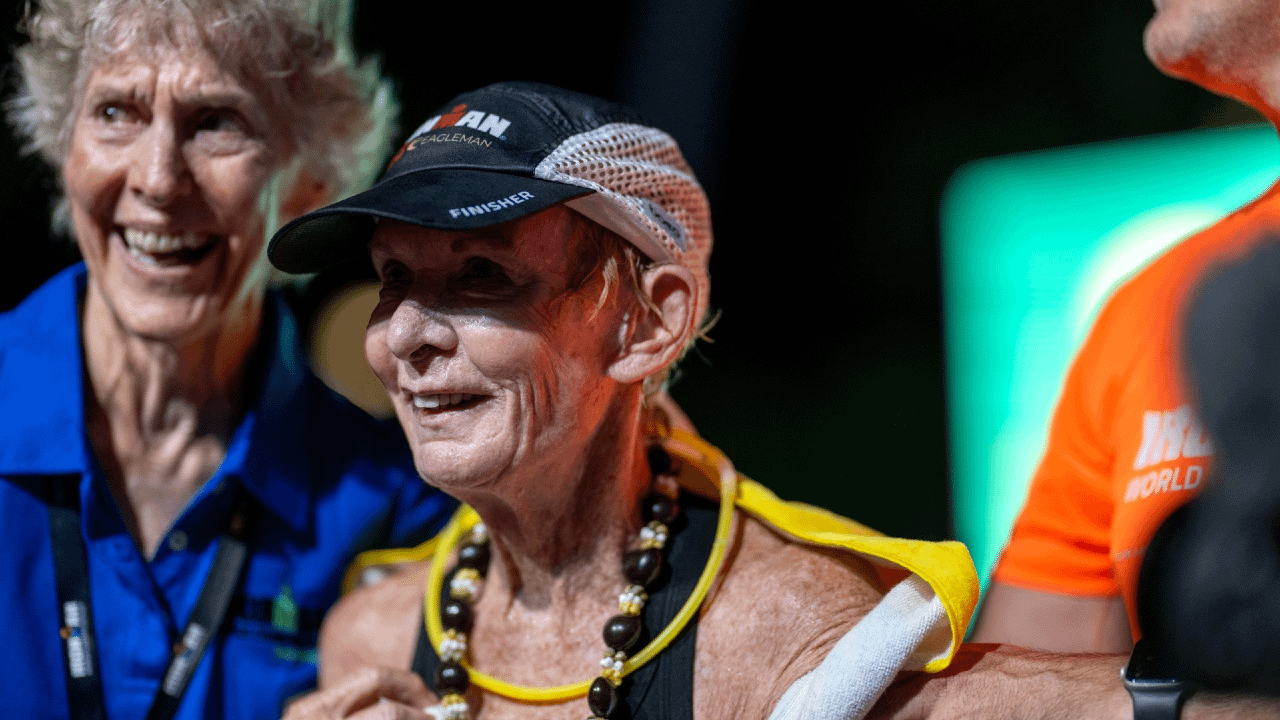

At 80, Natalie Grabow Goes the Distance at Kona

In punishing island heat, 80-year-old Natalie Grabow strung together 2.4 miles in the ocean, 112 on the Queen K, and a marathon to the lights on Alii Drive, finishing an Ironman in a single day. The clock and the course were not gentle. She kept going anyway.

The Ironman World Championship in Hawaii is legendary for a reason. The swim is rough-water Pacific, the bike bakes on black lava, and the run rises and falls through a convection oven. To close it out at 80, under the strict 17-hour cutoff, takes more than fitness. It takes resolve.

The day Hawaii turned up the heat

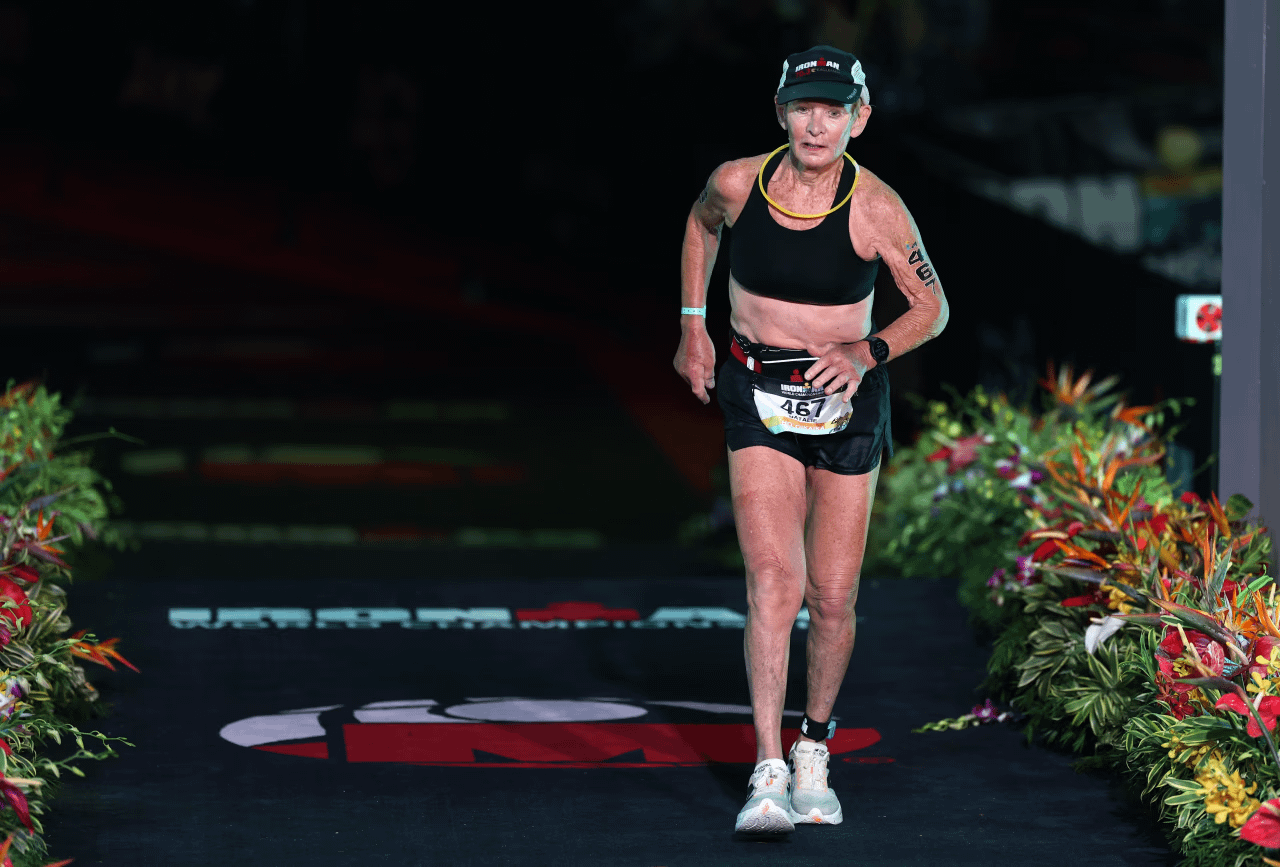

Conditions this year were a test for everyone, from professionals to age-groupers. Heat and humidity surged through the afternoon, and even front-runners faltered. Grabow stayed steady, ticking off aid stations and mile markers as the sun sank.

Starting the run in Hawaii and the temperature had climbed into 82 degrees Fahrenheit while the humidity was now over 70%.

That kind of weather turns pacing into survival. The strategy shifts from chasing splits to managing core temperature, electrolytes, and patience. It rewards athletes who can make hundreds of small, correct decisions when their bodies want to quit.

Setting the record straight

Some will call Grabow a first. She is part of something rarer than that. A decade ago, American triathlete Madonna Buder, known as the Iron Nun, became the oldest woman to finish an Ironman when she completed Ironman Canada at age 82. Her persistence over decades helped push the sport to recognize and expand older age groups.

Grabow belongs to that same lineage of boundary movers. Octogenarian women have proved the Ironman distance is not a young person’s monopoly, and every finish at 80-plus is another line in the record book of what is possible.

Why older athletes are rising

Look across endurance sports and a pattern emerges: while absolute world records have barely budged, age-group bests keep improving. Training knowledge is more widespread, recovery science is better, and communities of masters athletes share what works. Put simply, the playbook for staying fast longer is thicker than it used to be.

For athletes like Grabow, that means year-round aerobic consistency, strength to protect joints, heat acclimation ahead of Hawaii, and humility about pacing. It also means attention to the unglamorous details: hydration plans, sodium targets, and shoes that still feel good at mile 24 of the marathon.

The long day

Ironman’s 17-hour window creates its own kind of drama. The physical toll compounds as the hours add up. Muscles tighten after dark, and the final miles are as mental as they are mechanical.

Holding form into the night requires patience that most competitors learn only after years of races and setbacks. At 80, that patience becomes a superpower. Grabow used it, step by step, to outlast the course.

A growing, grayer start line

Ironman has slowly made space for older age groups as more athletes refuse the idea of a sporting expiration date. With that growth come questions about access and safety. The sport remains expensive, and race-day volunteers and medical teams carry a heavy responsibility as the field expands.

Still, the sight of octogenarians in the water at Kailua Bay changes what the rest of us believe about our own horizons. It reframes aging as an endurance event worth training for, not a cliff.