The first body was found in summer grass, not far from a huddle of cattle and a boundary of firs. In 1764, in the rugged Margeride hills of south-central France, a rural province began to whisper the same word each time another villager failed to come home: the Beast.

A province under siege

Between 1764 and 1767, dozens of people in Gévaudan, a sparsely populated corner that now lies mostly in the department of Lozère, were killed by a predatory animal or animals. County registers and parish notes traced a grim pattern. Victims were often poor and alone, many of them women and children, their throats torn, their bodies mauled. By the time the panic eased, roughly a hundred people were dead and more than two hundred attacks had been tallied.

The countryside had predators long before the Beast became a proper noun. Wolves were part of the landscape and the economy, hunted for bounties and blamed for vanished livestock. Yet the scale and brazenness of the Gévaudan killings felt unprecedented to locals. Attacks occurred in daylight in open pastures and along church paths, places where danger was supposed to be visible. Priests urged vigilance in Sunday sermons. Nobles organized communal hunts. Fear filled the gaps between fact and rumor.

When the king took notice

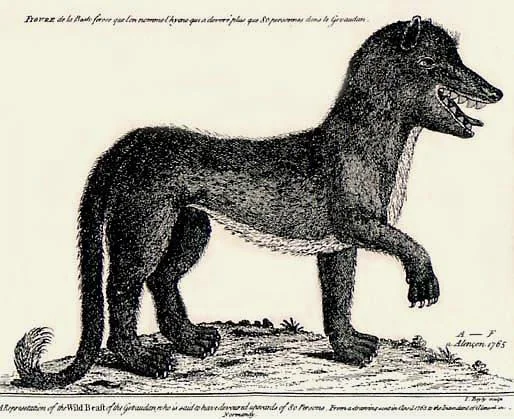

As reports grew, so did their reach. Prints circulated in Paris, pamphleteers embellished descriptions of a creature with a chest like a horse and a tail as thick as a pole. The court of Louis XV, attentive to public mood and reputational stakes, decided the provinces should not fight this battle alone.

First came soldiers. An army captain and his dragoons joined local nobles in vast battues, those rolling, days-long drives that tried to funnel forest game toward a fatal point. The hunts were spectacular, exhausting and mostly futile on rough volcanic ground threaded with ravines. When the animal slipped their nets and the killings continued, the crown sent a specialist.

In the fall of 1765, François Antoine, the king’s porte-arquebusier, arrived with trackers and large-bore guns. He killed an enormous wolf near the Abbey of Chazes, a trophy that was skinned, stuffed and driven triumphantly to Versailles. Officials declared victory. For a few weeks, Gévaudan could breathe.

A kill, then another

The relief did not last. Through late 1765 and into 1766, new attacks were recorded, sometimes miles from earlier sites, sometimes in clusters that suggested more than one animal. In June 1767, a farmer and innkeeper named Jean Chastel shot a large canid during a hunt in the woods near the hamlet of Sogne d’Auvers. Regional lore hardened quickly around the moment. Chastel became the man who ended the terror. After his shot, the killings stopped.

The hide of the creature Chastel killed reportedly went to Versailles, where it disappeared from the record. That loss is one reason the debate has never ended. Without a specimen to test, Gévaudan remains a forensic puzzle with too many variables and too much noise.

What was the Beast?

Theories range from the grounded to the cinematic. Most historians who have studied the case see no need for a supernatural explanation. The region had wolves, and wolves sometimes turn to people when their usual prey is scarce, when humans are small and isolated, or when animals are habituated to scavenging around settlements. Jean-Marc Moriceau, a historian of rural France and predation, has documented hundreds of wolf attacks across early modern France, a reminder that Gévaudan was horrific but not unimaginable for its time.

Other hypotheses try to account for the oddities in eyewitness descriptions. Some witnesses reported a russet coat with a dark dorsal stripe, tufted tail and broad head, features that do not fit a typical gray wolf. That has led to suggestions of a hybrid wolf-dog, an unusually large wolf with aberrant coloring, or an exotic escapee from a private menagerie, perhaps a striped hyena or a lion. Traveling animal shows existed along French roads, and accidents happened. But there is no surviving document that links an exotic carcass to the Gévaudan case.

Rabies was present in the period, yet it is an awkward fit for a problem that lasted three years. Rabid animals die fast, often within days. A single rabid wolf cannot plausibly account for the full span of attacks, though rabies could explain individual outbursts inside a wider pattern.

Human malice hovers at the edge of every famous mystery. A few investigators, then and now, have floated the idea of a killer who used dogs to mutilate victims, staging scenes to look like animal predation. The case file for Gévaudan is too scattered to prove it. Parish ledgers, notarial notes and letters offer glimpses, not a single chain of custody.

The most conservative reading remains the most convincing. Harvard historian Jay M. Smith, in his study of the episode, argues that the Beast was likely several wolves, perhaps unusually bold, amplified by a media ecosystem eager for a coherent narrative. That would align with the observed spread of attacks, the pauses and surges, and the way fear pressed communities to attribute unsolved disappearances to a single, named enemy.

How a story grows teeth

Gévaudan endures because it sits where nature, state power and storytelling meet. The crown’s involvement made the crisis national. Newspapers and broadsheets amplified each twist, from troop deployments to triumphant parades of pelts. Clergy and officials leaned into moral readings, urging repentance and discipline. Local elites used the hunts to demonstrate authority. Peasants weighed a more practical calculus, deciding whether to send children out with flocks or keep them home and lose a day’s wages.

Layered on top of the facts are embellishments that will not die. The idea that Chastel used a silver bullet, a detail that became catnip for novelists and screenwriters, is a later flourish that does not appear in the earliest records. The repeated claim that a single mutant creature shrugged off musket balls says more about the psychology of failure than the resilience of skin. When dozens of men comb forests for weeks and come up empty, the mind invents armor for the animal that escaped.

The legend is also tactile. The landscape of Gévaudan, with its basalt outcrops, pine-dark slopes and weather that turns hard in an hour, feels like a place where myths walk. Names have changed, parishes have merged, but the ground is stubborn. Shepherds still thread narrow lanes. Wolves, eradicated from France by the twentieth century, have returned from Italy into the Alps and Massif Central. Their presence is now managed through tight laws and heated politics. Each new predation on livestock turns up old arguments about risk, rights and rural life.

The afterlife of a terror

Modern culture has taken its turn. In 2001, director Christophe Gans turned the story into a lush, baroque action film, Brotherhood of the Wolf, a movie that blended court intrigue, martial arts and monster hunting into the kind of spectacle the eighteenth century might have envied. Novels, podcasts and museums in Lozère circle the same questions that animated the first pamphlets. What made these attacks feel so different, so singular, so personal to a region that already knew predators?

The truest answer is also the simplest. People died, often the most vulnerable ones. Communities tried everything they could think of, from prayers and bounties to battues and imported experts. In the end, an animal was shot and the killing stopped. If the Beast was many beasts, the relief was no less real for those who lived through it.