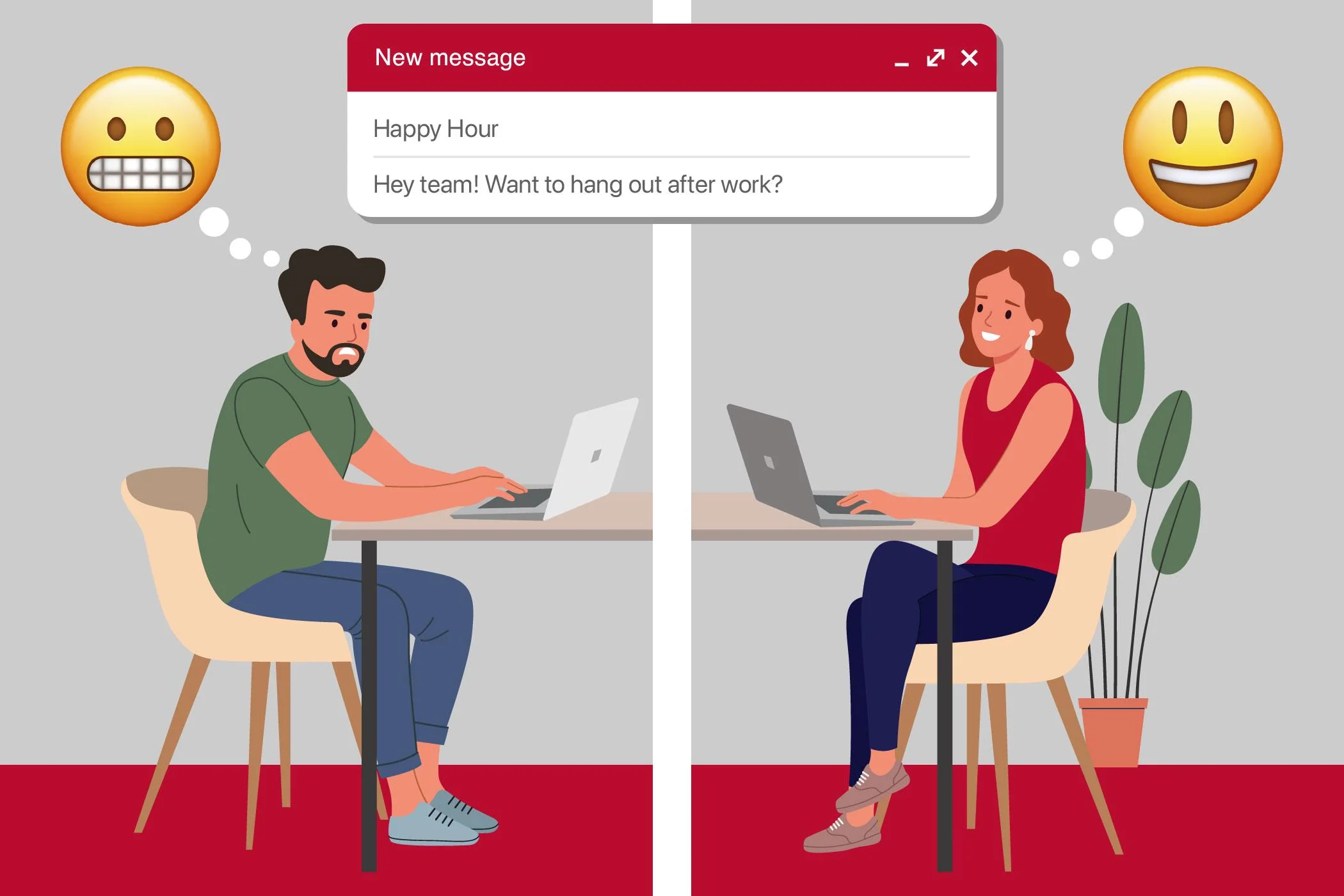

Happy hour is supposed to be easy. For some employees, an invite from colleagues feels like a small vote of confidence. For others, the same message triggers a churn of anxiety and a workday spent second-guessing how to respond.

After-work invites are not one-size-fits-all

Across many workplaces, post-shift gatherings are treated as culture builders, a casual space to bond and swap ideas away from the office. New research from the University of Georgia suggests that the impact of those invitations depends heavily on who is receiving them.

In a series of field and experimental studies published in Personnel Psychology, a team led by Joanna Lin, W. Richard and Emily Acree Professor of Management at UGA’s Terry College of Business, found that after-work invitations can lift some employees while weighing down others. Lin’s findings point to a double-edged reality: socially confident workers often feel included and energized, while those who struggle in group settings experience pressure and stress.

“We always think that social activity is so great, right? If you’re social with your co-workers, you feel energized and connected. But those invitations are not necessarily always good,” said Joanna Lin.

“There’s a social pressure that makes people feel like they have to say yes and need to be there. These outings seem like an obligation, even if they’re supposed to just be something fun.”

What the study found

Lin and colleagues surveyed hundreds of full-time employees, combining real-time diary methods with scenario-based experiments to capture how people feel from the moment an invite arrives. Among workers with higher social confidence, invitations tended to spark gratitude and a sense of belonging. Those emotions can feed morale and reinforce positive views of the workplace.

For employees who identify as shy or less confident in social settings, the pattern flipped. The invitation itself triggered worry about expectations, how to behave, and what others might think if they declined. Many reported becoming more tense and distracted during the workday as they weighed the decision, which eroded focus even before any gathering began.

“If you’re a social butterfly, you’re really good at interacting with others, so that doesn’t cause strife. When you already have a hard time being social, however, that sense of expectation contributes to the stress. You feel generally grateful for their gesture to include you in this social event but are worried about your social skills,” Lin said.

“There’s also that uncertainty. ‘If I say yes, how long will it take? Who else is going? Or if I say no, what are the consequences? Maybe my co-worker will be mad at me or I will feel left out.’ There are lots of psychological decision-making points that a simple invite causes,” Lin said.

Why invitations feel heavier than they look

In many offices, after-work gatherings sit in a gray zone between optional and expected. That ambiguity fuels the very stress Lin’s team documented. Even when no one means to apply pressure, the social calculus can feel high stakes to employees who fear the cost of saying no.

Power dynamics add another layer. An invitation from a peer can feel different from a note sent by a manager, especially if attendance has ever been tied to performance or visibility. The research highlights timing, source, and format as key variables that shape whether an invite feels welcoming or weighty.

“When we initiate this invitation, it has unintended consequences to employee performance for that day,” Lin said. “I think we should be mindful of when we give it. You may think you’re going to help this person by inviting them, but on the other hand, you could be making that person think ‘Oh my god, what am I going to do?'”

Rethinking how teams socialize

The takeaway is not to cancel social time but to design it for inclusivity. Leaders and organizers can preserve the upside of connection while reducing the downside of pressure by changing when, how, and where they gather.

- Keep most team-building during paid hours. A late-afternoon coffee or a walking meeting can deliver connection without taxing family time or commutes.

- State clearly that attendance is optional and not tied to performance or advancement. Put that commitment in writing so norms are explicit.

- Rotate formats beyond alcohol-centric settings. Consider volunteer shifts, brown-bag skill shares, short activity breaks, or quiet-friendly spaces where small groups can mingle.

- Be thoughtful about invitations from supervisors. Group announcements are usually lower pressure than personal pings from the person who evaluates your work.

- Create micro-connections inside the workday. Pair new colleagues for 15-minute introductions, run office hours, or schedule occasional cross-team stand-ups that respect boundaries.

These small design choices align with what the study observed: when uncertainty drops and expectations are clear, stress eases and the benefits of belonging have room to grow.

What employees can do for themselves

Agency matters too. The research suggests that recognizing your own preferences can help you navigate invitations with less friction. If group settings drain your energy, you can set a personal rule to attend shorter gatherings, arrive for the first half hour, or opt for smaller meetups that feel manageable.

It also helps to prepare a consistent, polite decline that you can use without second-guessing. You might propose an alternative that works better for you, such as a daytime coffee or a quick check-in during the week. Over time, these boundaries become understood, and colleagues tend to respect clarity.

For socially confident team members, the lesson cuts the other way. Extending an invitation can be generous, but the kindest outreach keeps stakes low and options open. A culture that normalizes no as a valid answer will often see more genuine yeses.