On a fresh ribbon of black rock still warm from Kīlauea, life returns on six legs. Before ferns lace the cracks or ʻōhiʻa roots find a foothold, a tiny, wingless cricket appears, eats what the wind delivers, and vanishes as soon as green takes hold.

Born of fire, built by wind

Hawaiʻi Island grows in pulses—curtains of lava spill from Kīlauea and Mauna Loa, harden into rippled pāhoehoe and jagged ʻAʻā, and leave behind an otherworldly plain. In the days and years after an eruption, this raw surface swings from scorching sun to chill night, with no soil, no shade, and almost no resources.

Yet even this seeming void is not empty. Trade winds rake the flow fields, carrying salt-laced sea foam from the coast and brittle fragments of leaves and bark from distant vegetation. On that windborne litter, an entire provisional food web is built.

The first settler: Caconemobius fori

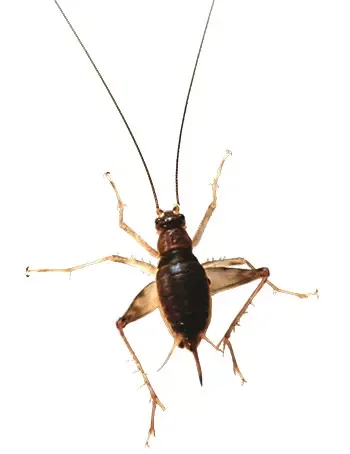

Meet the Kīlauea lava cricket, Caconemobius fori, known in Hawaiian as ʻūhini nēnē pele—“volcanic chirping cricket.” At roughly 9 millimeters long and darkly lustrous, it blends so well with fresh basalt that researchers liken it to Pele’s tears, the glittering drops of volcanic glass that pepper the flows.

These crickets are strictly nocturnal and wingless, but they spring astonishing distances when disturbed. Field surveys have found them astonishingly close to danger—sometimes within about a hundred meters of active vents—and notably absent from any spot shaded by established plants. Once a lava field gathers a fringe of vegetation, the crickets fade from view.

An ecosystem powered by air

In the absence of roots and leaves, C. fori survives on what the wind delivers. Researchers have documented the crickets feeding on windblown plant debris and even dried sea foam sifted inland by nearly constant trades. The result is a rare “neogeoaeolian” habitat—new ground sustained by airborne resources.

On calm nights the lava surface cools and tiny mantles of organic powder settle into cracks. That is when the crickets emerge, whiskers probing, picking clean the flow’s surface. By morning, the wind resumes, and the cycle repeats.

Where do they go when the green returns?

As ferns spread and ʻōhiʻa seedlings take root, the lava cricket disappears. Decades of observation have turned up a mystery as stark as the landscape itself: scientists have not recorded C. fori within several strides of established vegetation, and no one has definitively tracked where the population goes when plants arrive.

Some biologists suspect the crickets leapfrog to the newest flows, perpetually chasing bare rock. Others propose that remnant pockets persist in sunbaked cracks that remain too harsh for plants or predators, hiding in plain sight. What’s clear is that the cricket’s tenure is brief, its niche tied tightly to the island’s youngest skin.

Fieldwork after dark

Studying a creature that blends into basalt and forages only at night requires a certain stamina—and a few tricks. Entomologists walk the flows by headlamp, scanning for the quick, glossy flicker of movement among ropey lava toes and razor-sharp ʻAʻā.

To count them more reliably, researchers set pitfall traps and, surprisingly, bait them with cheese. The crickets are irresistibly drawn to it, a pungent stand-in for the nutrient-dense morsels that gust across the rock. By dawn, data in hand, scientists retreat before the sun turns the flows into a black anvil.

A barometer of succession

The lava cricket’s rise and retreat mirrors ecological succession itself. Bare rock hosts wind-fed scavengers, then lichens and mosses, followed by pioneering ferns and, eventually, hardy trees. Shade deepens, humidity rises, and a more familiar cast of insects, spiders, and birds returns.

In that progression, C. fori is both pioneer and placeholder, a signal that the island is between fire and forest. Its sudden absence doesn’t spell loss so much as a handoff—energy flows shift from the wind to photosynthesis, and a new balance takes over.

Island rarity, global insight

Hawaiʻi is famed for endemism—species found nowhere else—shaped by isolation and volcanic youth. It is also notorious for vulnerability: many native species have been lost or imperiled by habitat change, disease, and invasive predators and competitors. In that context, the lava cricket is a reminder that some native lives are bound to disturbance itself.

Studying such specialists offers clues to how life colonizes extremes, from cooling lava to newly deglaciated ground. The strategies C. fori uses—mobility without wings, camouflage, opportunistic feeding—are a primer in resilience. They also underscore how narrow a niche can be, and how quickly it can close.

What headlines get right

“This Mysterious Hawaiian Cricket Walks on Lava and Drinks Sea Foam.” — Newsweek (2022)

Behind the splashy line is a simple ecological truth. The cricket does not conjure food from barren rock; it harvests what the island’s winds deliver. In doing so, it links ocean and upland, atmosphere and stone, in a food chain as ephemeral as a gust.

Fire’s calendar, nature’s clock

Kīlauea’s rhythm will continue to reset the island’s clocks, laying down new fields for the lava cricket to claim. In years when eruptions stall, the habitat vanishes as surely as the flows cool; when lava runs again, a familiar nocturnal patter returns.

For now, C. fori waits at the margins of heat and darkness, its entire world measured in meters of new stone and grams of windblown dust. To stand on a recent flow at night is to enter its country: stark, silent, and unexpectedly alive.