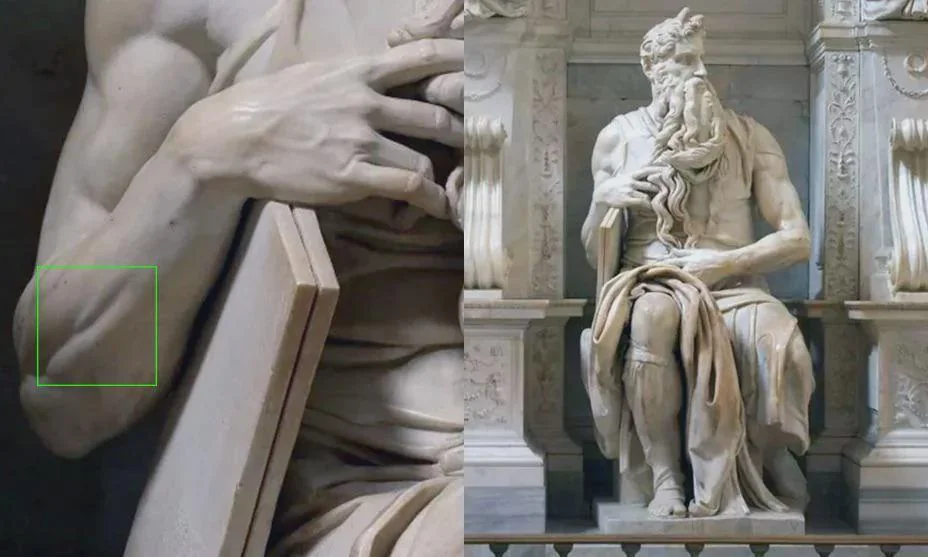

A raised pinky and a sliver of forearm muscle are easy to miss in Michelangelo’s Moses. Notice them, though, and the marble seems to breathe.

A masterpiece tuned to the smallest signal

Michelangelo’s Moses, carved around 1513–1515 for the long-delayed tomb of Pope Julius II, sits coiled like a spring in San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome. His torso twists, his beard spills in rivulets, and veins rope across his arms as if warmth still runs beneath the stone.

Amid this theatrical force is an almost microscopic flourish: Moses slightly lifts his right little finger. In response, a tiny band of muscle on the outer forearm swells into view—the extensor digiti minimi—rendered with such fidelity that modern viewers instinctively test their own wrists to feel it.

The biology inside the marble

The extensor digiti minimi is a slender muscle that runs along the ulnar side of the forearm. It helps straighten the fifth finger and contributes to wrist extension, threading to the hand through a narrow tunnel on the back of the wrist before joining the tendons that fan out to the little finger.

In most of us, it only becomes visibly defined when the pinky lifts or extends. That’s the tell. Michelangelo caught this fleeting contraction in stone, syncing a single, localized anatomical truth with the sculpture’s larger drama—Moses on the cusp of rising, energy gathering from fingertip to shoulder.

How did Michelangelo know?

Renaissance artists learned from the body as much as from books. Michelangelo studied anatomy intensively from his youth, observing the play of muscles in life and, with permission from clerics, studying the architecture of cadavers in Florence. He absorbed structure, not as separate facts, but as a living system of cause and effect: a twist of the torso, a shift in weight, a hand that begins to speak.

He also worked from models, as was standard practice. The discipline of the time was not a choice between memory and reference; it was a fusion. Live bodies supplied the data. Anatomy supplied the logic. The artist’s imagination supplied the synthesis—idealizing, editing, and coordinating dozens of micro-gestures into one coherent moment.

Great realism in Renaissance art was rarely copying; it was comprehension—knowing what a body does, and showing why it must do it.

Terribilità in the details

Moses is often cited as a summit of Michelangelo’s terribilità—an awe-inducing intensity that verges on the sublime. You see it in the ready-to-rise posture, the press of fabric against muscle, the tension in the neck, and the forward pull of his gaze, as if responding to a shock only he perceives.

Look closer and the small choices amplify the effect: the left leg drawn back to gain leverage, the right shoulder slightly forward to counterbalance, the robe gathered to free the knee. The pinky lift is one more click in that chain of cause and effect, an index of alertness made visible by anatomy.

Horns, tablets, and a translation that shaped an image

To modern eyes, Moses’s small horns can be startling. They trace to the Latin Vulgate translation of Exodus, which described Moses’s face as “horned” after meeting the divine—a rendering of the Hebrew root that can also mean “rayed” or “shone.” Medieval and Renaissance artists followed the text they knew, and Michelangelo joined that long iconographic lineage.

Tucked under Moses’s arm are the stone tablets, substantial enough to read as weight as well as symbol. Everything in the ensemble—horns, tablets, beard, posture—works as narrative, but all of it rides atop the sculptor’s anatomical orchestration. The result is a spiritual portrait grounded in physiology.

A legend at the knee and the truth of his temperament

For centuries, visitors have pointed to a mark on Moses’s right knee and repeated a legend: that Michelangelo struck the statue in frustration, demanding, “Why don’t you speak?” Whether or not that story is true, it tells us what viewers felt—that the figure seemed on the brink of life.

His intensity is not just myth. Late in life, frustrated with his Florentine (Bandini) Pietà, Michelangelo damaged the work with a hammer; it was later reassembled and finished in parts by the sculptor Tiberio Calcagni. Perfectionism, piety, and pressure formed a combustible mix in the artist’s studio, and sometimes the marble bore the blast.

What a pinky proves

Art history often celebrates the grand gesture—the heroic scale, the world-shaking commission. Moses has all of that. But it endures because of things you could miss: a tendon that swells only when a single finger lifts; a vein that tracks a pulse you cannot hear; a fold of cloth set to slip as a man rises.

Those details don’t merely embellish the whole; they generate it. They transmit the sculpture’s electricity from the smallest motor units outward, turning marble into a physiology lesson and, somehow, a biography of will.

Seeing with your hands

The most reliable test for Michelangelo’s little miracle is your own body. Rest your forearm on a table, gently lift your pinky, and watch the outer forearm. That slim band that stirs under the skin? The sculptor saw it, understood it, and made it speak for Moses.

- When the little finger rises, the extensor digiti minimi contracts and becomes visible on the ulnar side of the forearm.

- Michelangelo binds such micro-gestures to narrative, so the body’s mechanics carry the scene’s emotion.

The enduring lesson of close looking

Five centuries on, the statue still gives back whatever attention you bring to it. Stand before Moses and the loud things announce themselves: the size, the presence, the storm of it. Stay a little longer, and the small things take over—the pinky, the tendon, the breath you imagine between them.

That is the compact Michelangelo makes with us. He offers a world built from specifics, trusting that if we follow the details, meaning will rise to meet us.