James Knight’s 1719 Northwest Passage expedition wrecked at Marble Island in today’s Nunavut, where the survivors built a shelter and tried to overwinter. According to Inuit accounts later recorded by explorer Samuel Hearne, their numbers dwindled over two winters, and by the summer of 1721 all had died. The story is supported by Hearne’s interviews and by the remains of the ships and camp seen on Marble Island, rather than by any written message left by the crew.

Who was James Knight and why was he exploring?

James Knight was a veteran Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) governor and trader, probably born around 1640, which means he was “nearly 80” when he sailed in 1719. The HBC tasked him to sail north of 64 degrees to seek a Northwest Passage, expand trade, look for rumored copper and gold deposits, and assess whaling prospects. He left with two vessels, the Albany frigate and the sloop Discovery, in June 1719 (Dictionary of Canadian Biography).

What happened to James Knight’s 1719 expedition?

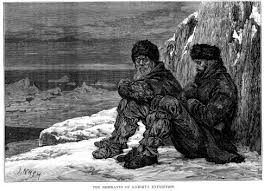

The ships ran aground and were lost at Marble Island, an isolated, low limestone island in western Hudson Bay. The stranded party, roughly 40 to 50 men, erected a house and tried to survive on local resources. Inuit later recounted that after the first winter, many were already dead. By the end of a second winter, only a handful remained.

“About 50 men were building a house in the late fall of 1719 after their ships had been wrecked… By spring their numbers were greatly reduced and by the end of a second winter only 20 men survived. Five lived until the summer of 1721 when they, too, died.” (DCB summary of Inuit testimony recorded by Samuel Hearne)

There is no authentic message from the crew. Knowledge of their fate comes from Indigenous oral history and later visits that observed wreckage and camp remains.

How do we know this and what evidence exists?

The core evidence comes from three sources:

- Inuit testimony recorded by Samuel Hearne (1769): Hearne, an HBC explorer, was guided to Marble Island and interviewed Elders who described the wrecks, the winter house, and the gradual deaths of the survivors (DCB).

- Material remains on Marble Island: Hearne reported two shipwrecks, a dwelling, and scattered wreckage in a cove. Later visitors continued to note relics at the site, consistent with an overwintering attempt after a double wreck (DCB).

- Contemporary HBC search reports: In 1722, Captain John Scroggs returned from the north with secondhand claims that “Every Man was Killed by the Eskimoes.” That early allegation was not borne out by later accounts or physical evidence, which point instead to starvation, disease, and exposure as the primary causes of death (DCB).

Unlike the later Franklin tragedy, Knight’s party left no written cairn notes, so there is no day‑by‑day record. The convergence of Inuit oral history with observed wrecks and a winter house provides the best supported reconstruction.

Who “saw the last man die while digging a grave”?

That vivid line comes from Inuit testimony Samuel Hearne recorded, often paraphrased today as “the last man died while digging a grave for his companion.” It should be understood as an oral recollection relayed to Hearne decades later, not as a European eyewitness report. The most reliable takeaway is the sequence, not the exact moment: a few men survived into the summer of 1721, then all perished (DCB). Given the subsistence limits of the region, Inuit observers had little capacity to feed or transport dozens of starving sailors through multiple seasons (overview of Inuit lifeways).

Were they killed by Inuit?

An early HBC report claimed wholesale killing by Inuit, but the later, more detailed record does not support a massacre. Hearne’s interviews emphasize wrecks, a wintering structure, dwindling numbers, and final deaths by the second summer. That picture matches what is known from similar Arctic disasters: starvation, scurvy, exposure, and infections, not organized violence, were the usual terminal causes when expeditions lost their ships and supply lines.

Key point: the best documented account, recorded in 1769 from Inuit Elders and cited by the DCB, describes attrition over two winters ending in 1721, not a single violent episode.

Was James Knight really nearly 80?

Yes. The HBC’s most seasoned hand, Knight was “said to have been nearly 80” when he sailed in 1719, and his long record as a carpenter, factor, and governor explains why he still secured command and financing for the voyage (DCB).

What happened to the ships and site today?

Hearne reported the remains of two wrecks on Marble Island in the 1760s, along with a dwelling site. The wrecks were never systematically surveyed in modern times, and no crew graves of European style have been documented there. Marble Island remains an evocative historic site on the western rim of Hudson Bay, and it figures in broader histories of the centuries‑long search for a Northwest Passage, which later included John Franklin’s 1845 disaster (overview).