Artemisinin was discovered in 1972 by Chinese scientist Tu Youyou, who isolated it from the sweet wormwood plant, Artemisia annua, after following a low temperature extraction hinted at in a fourth century medical text. It works because an endoperoxide bridge in the molecule is activated by iron inside malaria parasites, generating reactive radicals that rapidly kill the parasite. Today, artemisinin is the cornerstone of WHO-recommended artemisinin-based combination therapies for uncomplicated malaria.

What is artemisinin?

Artemisinin, also called qinghaosu, is a natural antimalarial compound from the leaves of Artemisia annua (sweet wormwood). It belongs to a class of sesquiterpene lactones that contain a distinctive endoperoxide bridge, the feature essential to its activity. Clinically, artemisinin is used via faster acting derivatives such as artesunate, artemether, and dihydroartemisinin, which are paired with a longer acting partner drug to form artemisinin-based combination therapies, or ACTs.

WHO recommends ACTs as the first line treatment for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in all endemic regions (WHO Malaria Guidelines).

How was artemisinin discovered?

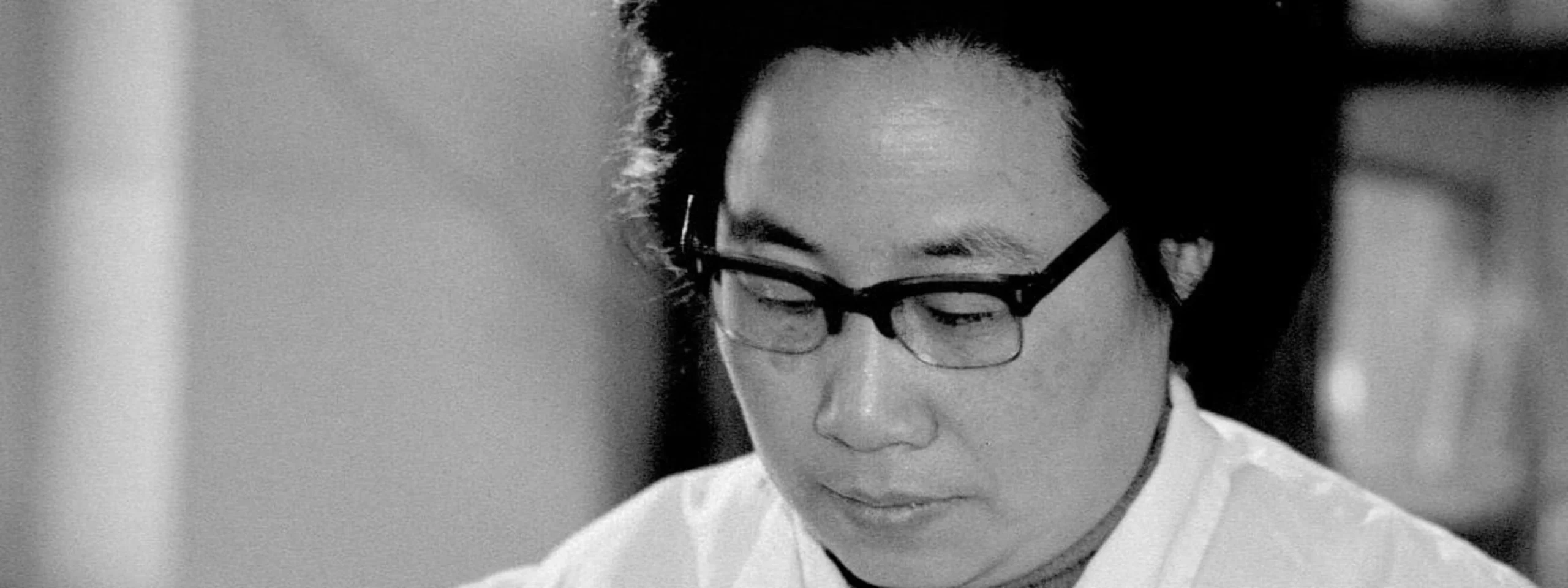

In the late 1960s, chloroquine resistance was spreading and a China-wide effort, Project 523, was launched to find new antimalarials. Tu Youyou led a team assigned to examine traditional remedies. A line in the fourth century handbook by Ge Hong, Emergency Prescriptions Kept Up One’s Sleeve, advised soaking fresh qinghao in cold water and wringing out the juice for fever. This suggested heat could destroy the active principle.

Tu’s team switched from hot extraction to low temperature solvents, notably ether, which boils at a lower temperature, and in 1972 isolated a potent antimalarial they named qinghaosu, later known internationally as artemisinin. Early safety checks included Tu and colleagues taking the extract themselves before small patient studies, followed by broader trials within the government program. The work was declassified and shared internationally in the late 1970s and 1980s, and artemisinin and its derivatives eventually transformed malaria treatment (Nobel Prize press release, 2015; Tu Youyou Nobel Lecture).

Tu summarized the breakthrough as “a gift from traditional Chinese medicine to the world,” acknowledging both textual clues and modern pharmacology in the discovery (Nobel Lecture).

How does artemisinin work?

Artemisinin contains an endoperoxide bridge that is cleaved when it encounters ferrous iron, abundant in the parasite’s digestive vacuole where hemoglobin is broken down. Cleavage generates short lived radicals that alkylate and damage essential parasite proteins and membranes, rapidly reducing parasite biomass. This fast action is especially effective against early ring stage parasites and helps relieve symptoms quickly.

Because artemisinin is cleared from the body within hours, it is combined with a longer acting partner drug, for example lumefantrine or piperaquine, to eliminate remaining parasites and reduce the risk of resistance (Medicines for Malaria Venture).

Why is artemisinin important?

The shift to ACTs in the early 2000s coincided with major gains in malaria control. Rapid parasite clearance, high efficacy against drug resistant P. falciparum, and good tolerability made ACTs the global standard. Intravenous artesunate replaced quinine for severe malaria because it lowers mortality more reliably when given promptly, based on randomized trials and policy updates from WHO and national programs (CDC malaria treatment; WHO Malaria Guidelines).

What are artemisinin-based combination therapies?

Common ACTs pair a fast acting artemisinin derivative with a long acting partner:

- Artemether–lumefantrine, widely used and dosed twice daily for three days.

- Artesunate–amodiaquine, a once daily three day regimen in many African countries.

- Dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine, once daily for three days, useful in some regions.

Choice depends on local resistance patterns, age and weight, and coexisting conditions. Monotherapy with an artemisinin derivative is discouraged because it increases the risk of resistance development (WHO guidelines).

What are the limitations and resistance issues?

Artemisinin’s short half life means it must be combined with an effective partner drug and taken for the full three day course. Side effects are usually mild, for example nausea or dizziness. For pregnancy, WHO recommends ACTs in the second and third trimesters, and allows their use in the first trimester when benefits outweigh risks, based on growing safety data.

Partial artemisinin resistance, characterized clinically by delayed parasite clearance, has emerged in the Greater Mekong Subregion and has been detected in parts of Africa. It is linked to mutations in the parasite’s kelch13 gene. ACTs remain effective in most settings, but vigilance, quality assured medicines, and appropriate partner drug selection are critical, and some programs are evaluating triple ACTs to safeguard efficacy (WHO resistance updates).

How is artemisinin supplied today?

Most artemisinin is extracted from cultivated A. annua, with supply buffered by semisynthetic routes that convert engineered yeast derived artemisinic acid to artemisinin, developed to stabilize availability and pricing (Nature, engineered yeast production).