A polar vortex split happens when the stratospheric polar circulation weakens and divides into two or more cold-core vortices, most often after a sudden stratospheric warming. This split can redirect the jet stream and open pathways for Arctic air to surge into mid-latitudes, raising the odds of widespread cold and snow in North America and Europe for several weeks. The exact locations and intensity depend on how the lower atmosphere responds to the disruption above.

What is the polar vortex?

The polar vortex is a large-scale, cold, cyclonic circulation that forms every winter over each pole. It extends from the lower atmosphere, the troposphere, into the stratosphere, roughly 10 to 50 kilometers above Earth. When it is strong and circular, it tends to confine the coldest air near the Arctic.

Definition: The American Meteorological Society defines the polar vortex as the circumpolar westerlies that encircle the poles, strongest in the stratosphere during winter, helping to contain cold polar air.

Meteorologists distinguish between the stratospheric polar vortex aloft and the tropospheric polar vortex below. They are related but can evolve differently. Disruptions aloft are often the trigger for notable surface weather changes.

What causes a polar vortex split?

The most common trigger is a sudden stratospheric warming (SSW), a rapid rise of stratospheric temperatures and pressure that weakens or displaces the vortex. Atmospheric wave activity from below, often associated with blocking high-pressure systems, pushes upward into the stratosphere and disrupts the vortex’s circulation.

Sudden stratospheric warming: The UK Met Office explains SSW as a dramatic stratospheric temperature jump that can reverse winds around the pole and break the vortex into multiple lobes.

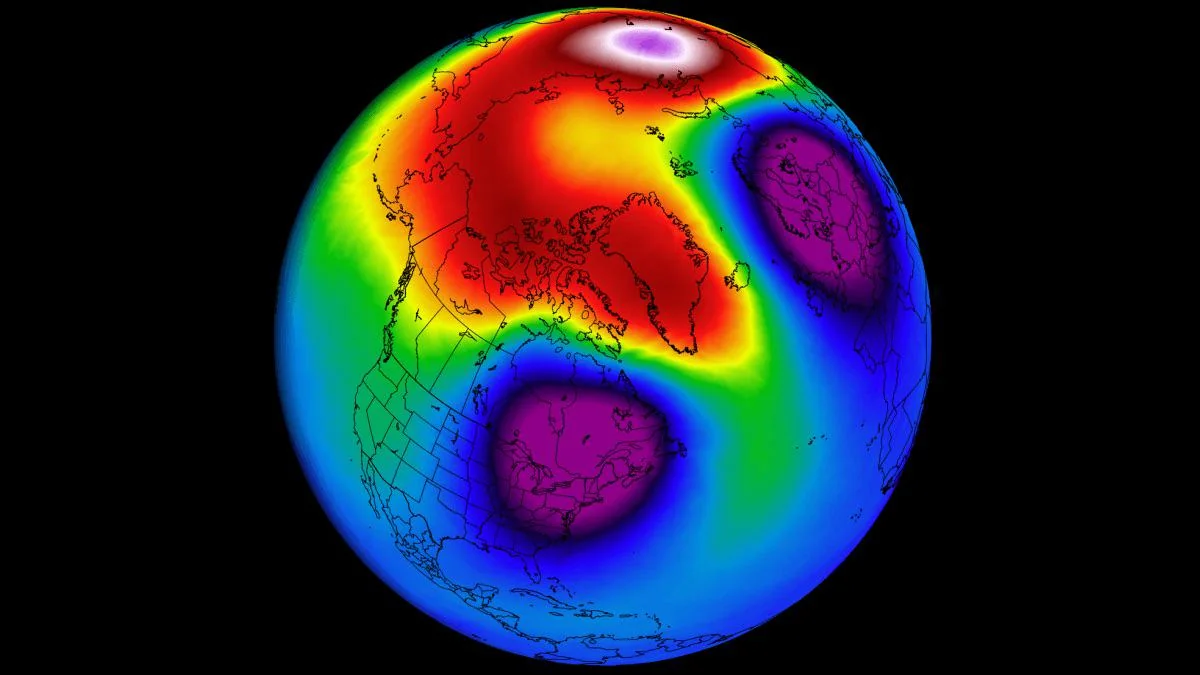

Recent analyses have linked a polar vortex split to an early-season SSW that deformed and divided the stratospheric vortex into two main cold cores over North America and Europe, setting up cold air routes into the mid-latitudes (Severe Weather Europe).

How does a split affect weather at the surface?

When the stratospheric vortex splits, the disruption can descend and alter the tropospheric jet stream, creating persistent troughs and ridges. Troughs favor northerly flow and cold air outbreaks, while ridges favor milder conditions.

- North America: One lobe positioned over Canada often drives Arctic air into the central and eastern United States while warming parts of far northern Canada ahead of the vortex core.

- Europe: A lobe near Scandinavia or northern Europe can feed colder northerly to easterly winds across the continent, with snow potential where moisture overlaps the cold.

- Storm tracks: Strong temperature contrasts can energize storms, but snowfall depends on moisture and low-pressure placement.

Typical timing: Following an SSW, surface impacts often emerge after a lag of about 2 to 6 weeks, consistent with a top-down influence through the atmosphere (ECMWF).

How long do the effects of a polar vortex split last?

Impacts typically unfold over several weeks. The disrupted circulation can support repeated cold shots, interspersed with brief milder resets as weather systems move. Historical analogs show January patterns with sustained cold in western and central Canada and frequent cold outbreaks into the northern and eastern United States and parts of Europe after early-season SSWs, although the exact pattern varies by year (SWE analysis).

How do scientists detect a split?

Meteorologists monitor wind and pressure at stratospheric levels, especially near 10 hPa, and track geopotential height and temperature anomalies. A split shows up as two low-height, cold cores separated by higher pressure in the stratosphere, often mirrored by developing low-pressure lobes below.

- Maps and colors: Stratospheric charts often use purple or blue for low heights and cold cores, and red or orange for high heights and warming. A split appears as two purple or blue centers with warm colors between them.

- Operational monitoring: Agencies such as the NOAA Climate Prediction Center and ECMWF provide real-time analyses and forecasts of the stratosphere and jet stream.

Is a polar vortex split linked to climate change?

Research is ongoing. Some studies suggest that Arctic amplification and changing wave patterns may influence the frequency or impacts of SSWs and vortex disruptions, while other work finds limited or regionally dependent signals. Major forecast centers caution that not every vortex split produces severe cold in the same places, and that surface outcomes depend on how the troposphere couples to the stratospheric disruption. The safest takeaway is that a split increases the risk of mid-latitude cold, but does not guarantee it for any specific city.

What does this mean for day-to-day forecasts?

Expect elevated odds of cold outbreaks and wintry storms along the favored storm tracks for a few weeks after a split, especially across Canada, the northern and eastern United States, and much of Europe. Local results will vary with each passing low-pressure system and moisture availability. For the most actionable guidance, check your national weather service and short-range forecasts, which assimilate the evolving stratosphere–troposphere state.