Yes. A blizzard can follow a tornado within hours, and in rare cases within about an hour, when a fast-moving, very strong cold front tied to a deep extratropical cyclone sweeps across the same area. Supercell thunderstorms in the warm, humid air ahead of the front can produce tornadoes, then the front passes, temperatures crash, rain changes to snow, and wind speeds increase to blizzard levels. The Great Blue Norther of November 11, 1911 is a classic case, with an F4 tornado in Rock County, Wisconsin followed shortly by blizzard conditions as Arctic air surged in.

What is happening when a blizzard follows a tornado?

The setup is a powerful extratropical cyclone with a sharp cold front. Ahead of the front sits a warm sector of unstable, moist air with strong wind shear, ideal for severe thunderstorms and sometimes violent tornadoes. As the front passes, temperatures can fall dozens of degrees in a short time. Precipitation flips from rain to snow, and strong pressure rises behind the front produce damaging northerly winds. If heavy snow and winds of at least 35 mph reduce visibility to a quarter mile for three hours, the event meets the definition of a blizzard.

In intense cold frontal passages, “warm sector” tornadoes and post-frontal snow can impact the same county on the same day, separated only by the rapid passage of the front and a fast temperature crash.

How does a tornado-to-blizzard transition work, step by step?

- Warm sector severe weather: Ahead of the cold front, buoyant air (high CAPE) and strong shear favor supercells that can spawn tornadoes.

- Frontal passage: The cold front surges through, often with a sharp wind shift and a rapid pressure rise.

- Temperature crash: Cold, dense air undercuts warm air, dropping temperatures below freezing, sometimes in minutes.

- Changeover to snow: Rain transitions to sleet and then snow, while wraparound moisture on the cyclone’s backside feeds banded snowfall.

- Blizzard conditions: Tight pressure gradients behind the front generate strong winds that combine with falling or blowing snow to produce whiteout conditions.

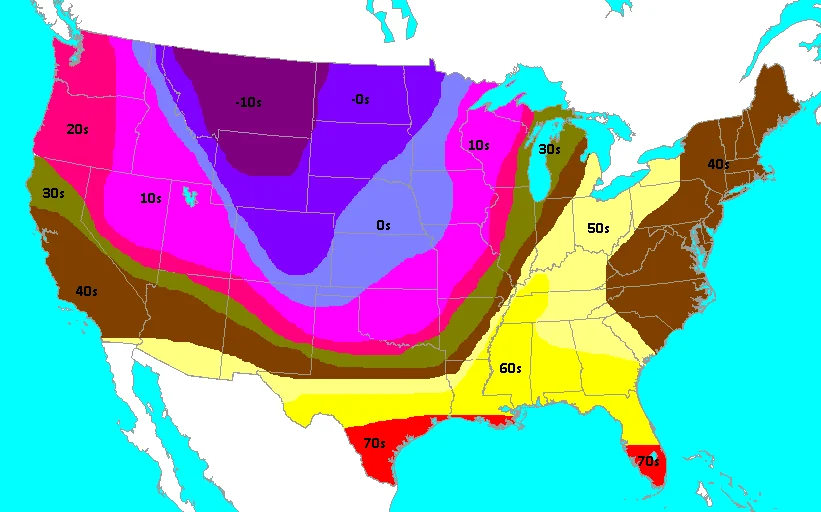

This sequence is most common in late autumn and early winter in the Plains and Upper Midwest, where strong Canadian air masses collide with lingering warmth from the south.

What happened during the Great Blue Norther of 1911?

On November 11, 1911, a historic cold front raced across the central United States. Many cities set record highs in the morning and record lows that night as Arctic air flooded in. In southern Wisconsin, an F4 tornado struck parts of Rock County near Janesville and Milton, and as the front blasted through, heavy snow and blizzard conditions followed soon after as temperatures plunged.

The event is documented as the Great Blue Norther of 1911, a day noted for extreme temperature swings and a rare pairing of severe convection and winter weather in quick succession. While tornado ratings from that era are assigned retroactively under the Fujita scale, the meteorological pattern that day is well recognized: a deep low, a surging front, and a rapid transition from warm-season to winter hazards.

Many Midwestern locations recorded both record highs and record lows on 11/11/1911, a signature of the front’s extraordinary intensity.

How fast can temperatures drop in these setups?

Very quickly. Deep, dense Arctic air can produce extraordinary short-term swings when a front arrives. Modern observations underscore what is physically possible:

- Denver recorded a 37 degree Fahrenheit drop in one hour during a December 2022 Arctic front, and a 75 degree fall over 18 hours as documented by the National Weather Service via ASOS at Denver International Airport.

- Spearfish, South Dakota holds the world record for the fastest recorded temperature change: a 49 degree rise in two minutes due to a Chinook wind, followed by a rapid plunge when the wind died.

- Rapid localized warming is also possible in rare heat burst events, highlighting how quickly atmospheric processes can shift surface temperatures.

These examples show that hour-to-hour swings large enough to flip rain to snow, even after tornadic storms, are meteorologically plausible when the synoptic pattern is extreme.

How rare is a blizzard right after a tornado?

The overlap in one county or city within an hour or two is unusual, but the broader pattern of severe storms ahead of a front and winter weather behind it on the same day is not rare in strong fall and winter cyclones. The Upper Midwest, Great Plains, and Great Lakes are most prone when powerful Canadian air masses surge south and interact with Gulf moisture. Events like the Great Blue Norther remain memorable for combining high-impact hazards in rapid succession.

What are the limitations and caveats?

- Local timing varies: Even during extreme events, the exact interval between a tornado and subsequent blizzard conditions depends on storm speed and track.

- Classification standards: “Blizzard” has a strict definition. Some events produce heavy snow and high winds without meeting the three-hour visibility threshold.

- Historical ratings: Early 20th century tornado intensities are assigned retroactively from damage surveys, so F-scale values reflect best estimates, not direct wind measurements.

If you encounter rapidly deteriorating conditions after severe storms, trust warnings and forecasts. Modern radar, numerical models, and National Weather Service alerts can often signal these sharp transitions many hours in advance.