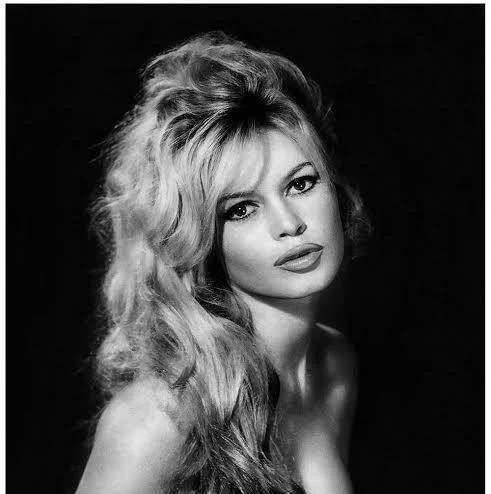

And God Created Woman is a 1956 French drama directed by Roger Vadim and starring Brigitte Bardot and Jean-Louis Trintignant. It became controversial for its frank eroticism and depiction of a free-spirited young woman, drawing censorship and condemnation in several countries while turning Bardot into an international star. The film’s sensual marketing, cuts for different markets, and moral outcry helped define its reputation as a provocative landmark of postwar European cinema.

What is And God Created Woman?

And God Created Woman (French: Et Dieu… créa la femme) is a Saint-Tropez–set feature produced by Raoul Lévy and released in France in 1956, with a U.S. release following in 1957. Vadim directed and co-wrote the screenplay. The film introduced Bardot to U.S. audiences and paired her with rising actor Jean-Louis Trintignant and German star Curd Jürgens as the wealthy Eric Carradine.

Often cited as Bardot’s breakout, the film made her an international sex symbol and popularized Saint-Tropez as a glamorous destination (Encyclopaedia Britannica).

For credits, release details, and production background, see the film’s overview on Wikipedia and the studio notes at TCM.

What is the film about?

The story follows Juliette Hardy (Bardot), an 18-year-old orphan whose beauty and uninhibited behavior unsettle the small coastal town of Saint-Tropez. To avoid being forced to leave the town, she impulsively marries Michel Tardieu (Trintignant), a decent, hard-working local. Her desire and attention, however, oscillate between Michel, his more worldly brother Antoine, and the influential businessman Eric Carradine.

Jealousy, class tension, and the town’s moral codes collide as Juliette’s sexuality becomes the catalyst for conflict. The film culminates in a feverish dance and violent confrontation that push the couple to the brink before a tentative reconciliation. A fuller synopsis is available via TCM.

Why was it controversial?

The controversy centered on the film’s open celebration of Bardot’s sensuality, its suggestive dancing, and Juliette’s refusal to conform to conservative expectations. In the United States, the movie was marketed as a daring continental import and arrived amid active moral scrutiny of foreign films. Cuts were made for certain markets, and church-linked watchdogs denounced the content.

The National Legion of Decency listed And God Created Woman among its condemned titles, reflecting 1950s U.S. concerns about on-screen sexuality (Legion of Decency records).

Despite the pushback, the film drew strong curiosity and became a hit in art houses. Its notoriety, and Bardot’s image on posters and lobby cards, helped sell the idea of foreign-language cinema as sophisticated and risqué to American audiences, a point noted in retrospectives by institutions such as the Britannica and in film histories summarized on Wikipedia.

Why is And God Created Woman important?

- Star-making turn for Bardot: The film established Bardot as a global icon, shaping media narratives about modern female sexuality in the late 1950s (Britannica).

- Breakthrough for Trintignant: It was an early showcase for Jean-Louis Trintignant, who went on to a major international career, including roles in A Man and a Woman and Amour (Britannica).

- Shifting boundaries on screen: The movie helped normalize more candid depictions of desire in mainstream European cinema and in imported films in the U.S., even as it met resistance from censors and religious groups.

- Cultural footprint: The Saint-Tropez setting became synonymous with jet-set leisure, and the film’s imagery, especially Bardot dancing barefoot, became emblematic of postwar European chic (TCM).

How do critics view it today?

Modern assessments tend to separate the film’s cultural impact from its artistic merit. Many critics see it as a star vehicle, more important for launching Bardot and for its scandals than for narrative or stylistic innovation. Profiles of Vadim often argue that his cinema prized sensual surfaces and celebrity mystique over rigorous storytelling or formal experimentation, a view summarized in director overviews such as Senses of Cinema.

Contemporary retrospectives often conclude that the film is historically significant, especially for Bardot’s persona and 1950s sexual politics, even if it feels dated in tone and gender dynamics by current standards (Senses of Cinema, TCM).

Who made it and where does it fit in film history?

Roger Vadim was a French writer-director associated with sophisticated, erotic star vehicles in the 1950s and 1960s. He was married to Bardot during the period surrounding the film’s production. Although contemporaneous with the French New Wave, Vadim’s work is generally discussed as parallel to, not part of, that movement’s formal innovations (Senses of Cinema).

The film also connects to a later Hollywood remake directed by Vadim in 1988, starring Rebecca De Mornay, which underlined the original’s durable, if contested, premise about desire and moral double standards.