When Eye Pigment Turns Against You: The Hidden Glaucoma

A little-known syndrome stalks young myopes, then spikes pressure overnight

It usually starts with a halo. Streetlights bloom like oil slicks, vision wobbles after a workout, and a dull ache settles behind one eye. Then pressure, the kind you cannot rub away. By the time many people learn the name for it, pigment dispersion syndrome, they have already learned something harsher, that eye color can turn into shrapnel.

The internet recently surfaced a visceral description of this condition, the iris pigment, the tiny granules that give eyes their color, can shear off, circulate in the eye, and choke the drain that keeps ocular pressure stable. The short version sounds like a horror story. The long version is more interesting, and more urgent, because it reveals a gap in how we think about glaucoma and who we assume is at risk.

Up to about one in three people with pigment dispersion eventually develop pigmentary glaucoma according to ophthalmic references, a serious, sight threatening form of open angle glaucoma.

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide, as the National Eye Institute reminds us, yet most public advice focuses on aging and diabetes. Pigment dispersion often shows up earlier, in people who are near sighted and in their 20s, 30s, or 40s. The stereotype of glaucoma as a disease of grandparents leaves many younger patients out of the conversation.

The anatomy of a quiet failure

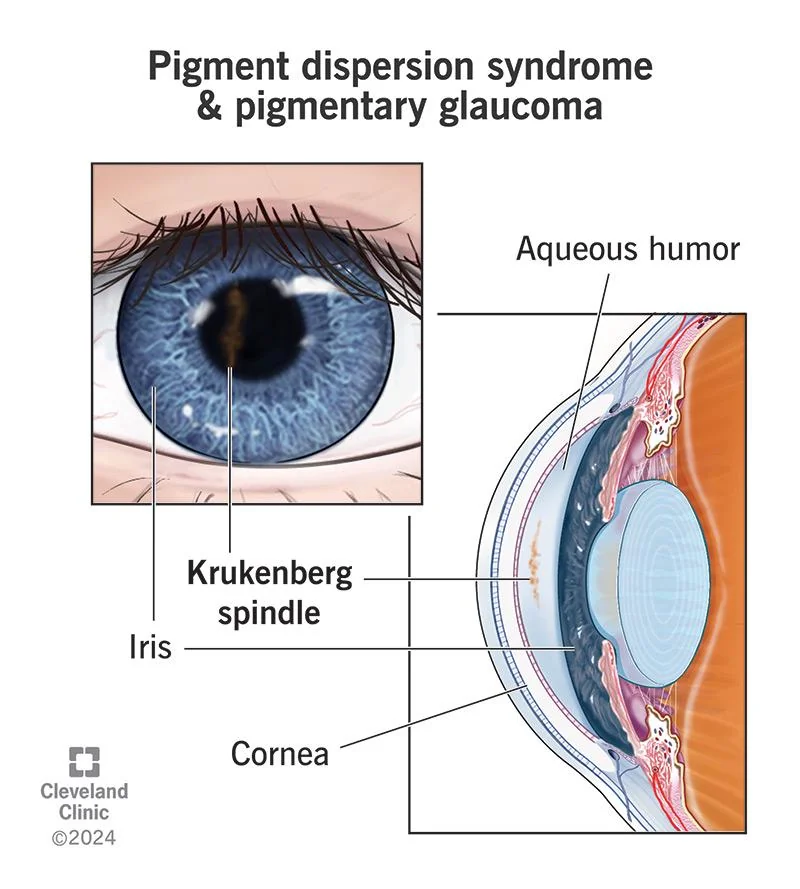

Anatomy explains the mischief. In some eyes, the iris bows backward slightly. During normal pupil movement, and especially during vigorous activity, the back of the iris rubs the lens support fibers, the zonules, showering microscopic melanin into the fluid that fills the front of the eye. Those particles get trapped in the trabecular meshwork, the fine sieve that drains eye fluid, and pressure rises.

Clinicians can often spot the clues. A vertical dusting of pigment called a Krukenberg spindle on the cornea. Spoke like areas where light passes through the mid peripheral iris, transillumination defects. A heavily pigmented drainage angle on gonioscopy. None of this is visible in the mirror, which is why the syndrome is both underdiagnosed and surprising when named.

Who is most likely to hear that name? The pattern crops up more in people with moderate to high myopia, often men, often with lighter irides, though it is not exclusive to any group. Family history matters. The American Academy of Ophthalmology’s EyeWiki notes that pigment dispersion is not common, exact prevalence is uncertain, yet among those who have it, about 10 to 35 percent progress to pigmentary glaucoma over time, a range echoed by patient facing resources at the Glaucoma Research Foundation.

Exercise can trigger pigment “storms,” short lived pressure spikes after activities like running or playing basketball, because pupil movement and iris movement increase pigment release.

This does not mean people should avoid exercise altogether. It does mean that unexplained halos, blurred vision after exertion, or recurrent eye pain deserve an appointment with an ophthalmologist, not a shrug. Pressure spikes can damage the optic nerve silently before symptoms shout.

Treatments, controversies, and the DIY trap

The toolbox looks familiar to anyone who follows glaucoma care. First line medications, prostaglandin analogs like latanoprost, brand name Xalatan, and beta blockers like timolol, lower eye pressure. Selective laser trabeculoplasty can help the eye’s drain work better. In advanced or uncontrolled cases, minimally invasive glaucoma surgery or more traditional filtering procedures come into play. These are not exotic options, they are well studied pathways tailored to individual eyes.

Then there is laser peripheral iridotomy, a pinhole opening at the edge of the iris. The logic is tidy, relieve the reverse bowing of the iris, reduce contact with the zonules, reduce pigment release. The evidence is less tidy. While some ophthalmologists believe it helps selected patients with a particularly concave iris configuration, reviews summarized by the AAO suggest that iridotomy does not consistently prevent progression to glaucoma in pigment dispersion. The EyeWiki entry on pigmentary glaucoma captures this nuance, iridotomy may flatten iris contour, but proof that it changes long term outcomes is limited.

These debates matter because they highlight the core risk, lost time. In a condition that can simmer for years before it burns, interventions that stabilize pressure and preserve the optic nerve are the point. Chasing unproven fixes is not.

Never put homemade solutions in your eyes. Stories of do it yourself enzyme drops or industrial solvents are compelling, they are also dangerous and unsupported by clinical evidence.

If the internet loves anything, it is the clever hack. Eyes do not reward improvisation. Corneal ulcers, chemical injuries, and masked infections are too high a price for a placebo, let alone a misfire. If pain and halos are weekly visitors, that is a signal to escalate with your doctor, not to self experiment.

Why this matters now

Look around any city and you see the trendline. Myopia is rising globally, with some regions reporting rates over 80 percent in teenagers and young adults. More myopia means more people with the anatomical setup that makes pigment dispersion possible. The burden is not just more glasses, it is more young adults who could edge into glaucoma during their most productive decades.

There is another reason to pay attention. Pigmentary glaucoma is a variant of open angle glaucoma, which too often gets diagnosed late. Catching pigment dispersion early, sometimes during a routine exam when a clinician notices a Krukenberg spindle or angle pigmentation, creates a window for simple steps that change the curve, medication adherence, monitoring, targeted laser, and, in specific cases, thoughtful surgery.

For patients and families, the mindset shift is practical, not panicked. You do not need to memorize anatomy to protect your vision. You do need to respect subtle symptoms and keep up with exams if you fit the profile.

- If you are moderately to highly myopic, especially if you notice halos or blur after exercise, schedule a comprehensive eye exam that includes pressure measurement and a dilated view of the optic nerve.

- Ask whether your eye doctor sees signs of pigment dispersion, corneal pigment, iris transillumination, or a heavily pigmented drainage angle.

- If diagnosed, discuss evidence based options to reduce pressure and pigment release, and set a schedule for visual field testing and optic nerve imaging.

- Keep perspective, many people with pigment dispersion never develop glaucoma, and with treatment, many with pigmentary glaucoma maintain useful vision for life.

Public health messaging has learned to say that glaucoma often has no symptoms. True, but incomplete. Pigment dispersion sometimes does have symptoms, especially around exertion, and those symptoms can be a useful alarm if people know to listen.

There is also a research story unfolding. As imaging gets better, ophthalmologists can map the iris contour and the drainage system in finer detail. Trials are clarifying which interventions alter the disease course and which only alter the optics of the iris without protecting the nerve. The more we understand who progresses, and why, the better clinicians can move beyond one size fits all algorithms borrowed from other glaucoma types.

In the meantime, hold two thoughts. The first is hopeful, this is a manageable condition in many cases, with tools that already exist. The second is motivating, waiting until your vision announces the problem can close doors. Eyes are not forgiving about time.