On crisp evenings in the 1700s, respected astronomers pointed small refractors at a glaring white lantern in the west and swore they saw a tiny companion flitting beside it. They gave it a name, sketched orbits by candlelight, and argued in journals. Then the companion stopped showing up.

There is no confirmed moon of Venus, and that is the more interesting story.

Every few years the “lost moon of Venus” resurfaces, a great headline with a long tail. The alleged satellite even has a name, Neith, bestowed in the late 19th century for the Egyptian goddess linked to the planet. Reports of a Venusian moon clustered in the 17th and 18th centuries, when observers like Giovanni Cassini and James Short recorded a faint dot near the brilliant disk and others claimed to see it again on different nights. In all, historical compilations tally more than a dozen sightings over two centuries, yet they refused to line up into a coherent orbit.

The “moon” appeared, vanished, reappeared months or years later, and never moved the way a bound satellite must.

When 19th‑century astronomers revisited the claims with better star charts and more reliable optics, the mystery deflated. Many of the best‑documented observations lined up with background stars that happened to sit close to Venus on the sky, a brutal test for small telescopes that struggled with glare and internal reflections. Others were almost certainly optical ghosts, faint mirror images created by the lenses themselves. By 1887, Belgian astronomer Paul Stroobant had published a systematic autopsy linking famous “sightings” to specific stars. Neith joined the respectable pantheon of astronomical mirages, alongside Martian canals and the nonexistent planet Vulcan.

Still, the idea endures. It is wonderfully human to prefer a hidden world to a trick of optics. But the deeper reason Venus is moonless may be dynamical, not just historical.

The 1700s frenzy that birthed Neith

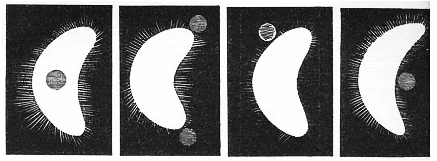

Context helps. Early refractors were marvels for their time, and land‑mark astronomy was done with them, yet they came with quirks that modern observers forget. Bright targets produce halos, off‑axis reflections, and spurious companions. Venus is the worst possible stress test, a sunlit mirror that dazzles the eye and the eyepiece.

- Background stars near Venus were easily masked or distorted by glare, then rediscovered as “companions.”

- Internal reflections in lens stacks created ghost images offset from the planet, faint and moon‑like.

- Atmospheric seeing, the shimmer of turbulent air, split the planetary disk and nearby light into dancing fragments.

None of that indicts the observers, it indicts the tools. Which is why the absence of credible modern detections matters. Orbital missions and precision surveys have spent decades in Venus’s neighborhood. NASA’s Magellan mapped the surface by radar, ESA’s Venus Express orbited for eight years, and JAXA’s Akatsuki is there now. None has seen a moon or a ring system.

If a natural satellite larger than a few kilometers circled Venus today, the combined scrutiny of spacecraft, radar, and all‑sky surveys would almost certainly have revealed it by now.

Could Venus keep a moon even if it had one?

Here the planet itself argues against companionship. Venus rotates backwards, very slowly, with a sidereal day of about 243 Earth days, longer than its year of 225 days. That lethargic spin changes how tides transfer energy between a planet and a satellite. For a typical prograde moon around a slowly spinning planet, tidal interactions tend to sap the moon’s orbital energy and shrink its orbit over time, often ending in a crash.

Venus’s day is longer than its year, and that sluggish, retrograde spin is hostile to long‑lived moons.

Simulations suggest Venus may have had moons in the deep past, born from giant impacts much like the one that created Earth’s Moon. In some models, a first moon spiraled inward and splashed back, depositing angular momentum that helped stall and even reverse the planet’s rotation, after which a second moon formed and met a similar fate. The upshot, as summarized by work presented by Caltech researchers Alex Alemi and David Stevenson, is stark: Venus could have been a moon‑maker that could not keep what it made. You can browse an accessible overview via the Caltech news archive and related research on planetary tidal evolution.

There is also the Sun to contend with. Closer to the star, solar tides and gravitational nudges from Mercury and Earth are stronger, which destabilizes distant orbits and shrinks Venus’s comfortable zone for satellites. The planet’s Hill sphere, the region where its gravity dominates, is smaller than Earth’s, giving any would‑be moon less room to roam.

Could a small asteroid be captured for a while? Possibly for short spans. But long‑term, the math stacks the deck against permanence. That matches the observational record: centuries of careful watching, and silence.

What we actually see today

Venus does have company of a different kind. In 2002, astronomers found a co‑orbital asteroid, 2002 VE68, that loops around the Sun in near‑lockstep with Venus in a curious dance called a quasi‑satellite orbit. It is not bound to Venus the way a true moon is, yet from the planet’s vantage point it would appear to hover nearby for years. In 2023 the International Astronomical Union embraced popular culture and formally nicknamed it Zoozve, a wink to an xkcd comic that misread the asteroid’s designation. It is a perfect example of how orbital geometry can play tricks on intuition.

Between quasi‑satellites, faint zodiacal dust rings along planetary orbits, and the raw dazzle of Venus itself, there are many ways to conjure a companion that is not there. The difference now is that we can test the claim. High‑cadence sky surveys like Pan‑STARRS and the Vera C. Rubin Observatory map moving objects across the inner solar system. Spacecraft at Venus watch for occultations, rings, and dust. If a new moon shows up, it will not hide for long.

So why does the rumor persist? Partly because we love the idea. Partly because Venus, more than any other planet, is an optical prankster, the same bright impostor behind so many historical “UFOs.” Mostly because the absence of evidence is not as clickable as the promise of rediscovery. But science keeps score. When the observations are inconsistent, when the dynamics are unforgiving, when better instruments see nothing, the simplest conclusion is usually the right one.

The phantom moon is a mirror trick, and the mirror is us, our tools, and our appetite for wonder. The good news is that wonder survives scrutiny. In the next decade, NASA’s VERITAS orbiter, the DAVINCI probe, and ESA’s EnVision mission will turn their attention to Venus’s surface, atmosphere, and interior. They are unlikely to find a moon, but they will tell us why a world so similar in size to Earth became so profoundly different. That is the real mystery worth reviving.