Under a microscope in a Texas lab, tired human cells brightened as their energy returned. The spark did not come from a drug or a gene edit. It came from a fresh supply of mitochondria, the tiny power units that keep cells alive.

Biomedical engineers at Texas A&M University report they have found a way to coax healthy donor cells to manufacture extra mitochondria, then share the surplus with nearby cells that are damaged or old. In lab experiments, the recipients regained energy production, performed better, and were less likely to die when stressed. The work, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, adds momentum to a fast-moving area of biology that treats mitochondrial decline as a core feature of many diseases and of aging itself.

Mitochondria generate most of the chemical energy that cells use. When they falter, tissues slow down. The effect shows up across the body, from the heart to the brain to skeletal muscle. It is a hallmark of age and a driver of disorders that include cardiomyopathy and neurodegeneration. Scientists have long tried to revive failing mitochondria with drugs or by nudging cells to make more. The Texas A&M team took a different path. They engineered the conditions for cells to pass replacements hand to hand.

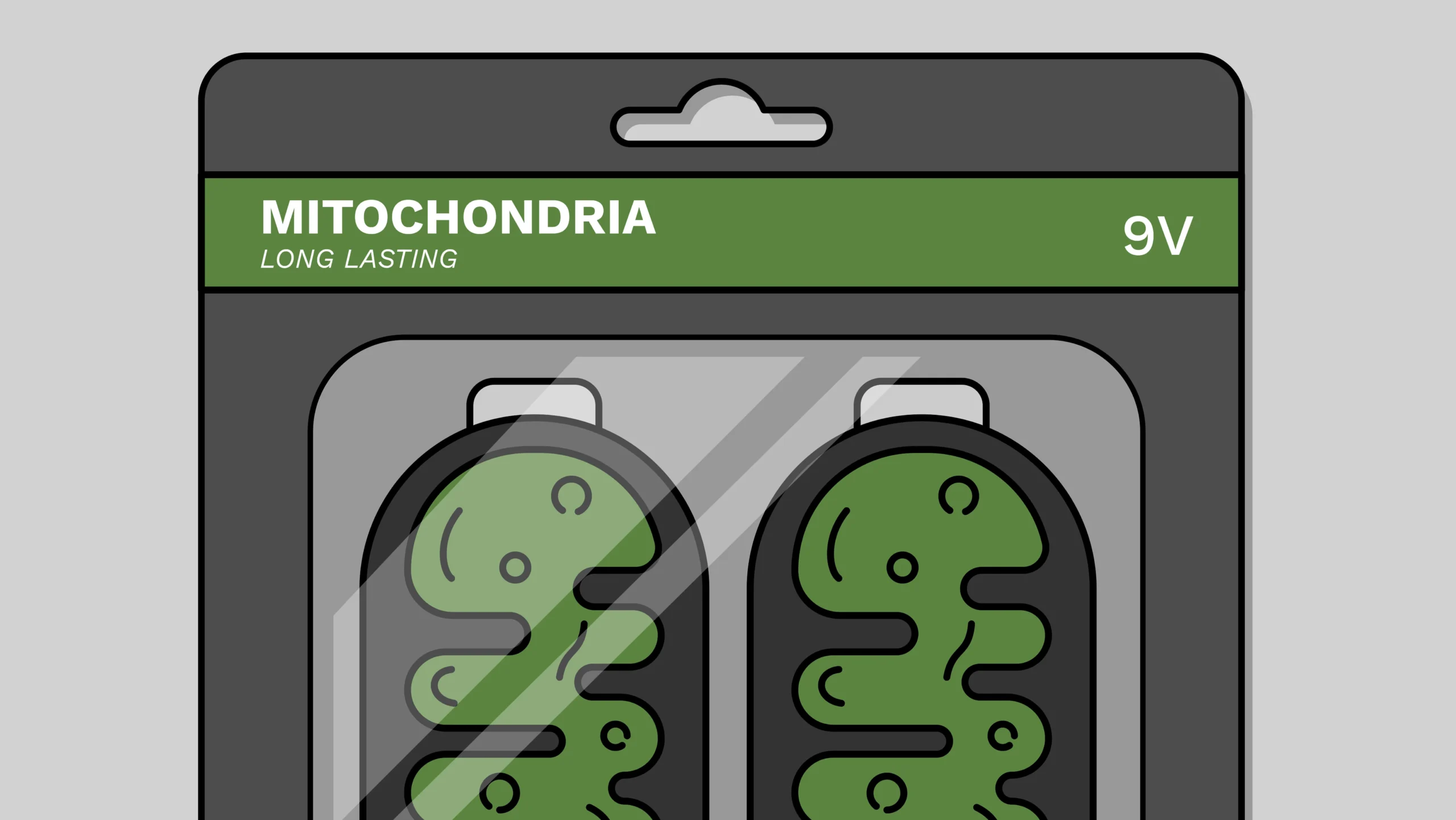

“We have trained healthy cells to share their spare batteries with weaker ones,” said Akhilesh K. Gaharwar, professor of biomedical engineering at Texas A&M, who led the study with doctoral researcher John Soukar.

How the swap works

The researchers used two ingredients. First, human stem cells that naturally talk to their neighbors and, under the right conditions, can hand off mitochondria. Second, a nanoscale catalyst that pushes those stem cells to produce far more of the power units than usual.

The catalyst is a microscopic particle with a crystalline, flower-like shape known as a nanoflower. In this case it is made from molybdenum disulfide, an inorganic compound more familiar from electronics than from medicine. Each particle is roughly 100 nanometers across, large enough to linger inside a cell rather than wash out quickly.

When the team exposed stem cells to the nanoflowers, the cells doubled their mitochondrial output. Placed next to damaged or aging cells, these primed donors transferred two to four times more mitochondria than untreated stem cells. In recipient cells, the incoming organelles bolstered energy production, restored function, and improved survival when the cells faced chemical insults that normally trigger death.

“The several-fold increase in efficiency was more than we could have hoped for,” said Soukar, the paper’s lead author. “It is like giving an old electronic a new battery pack. Instead of tossing them out, we are plugging fully charged batteries from healthy cells into diseased ones.”

Why this is different

Cells can exchange mitochondria on their own. Scientists have seen transfers during development, after injury, and in certain disease states, often via threadlike bridges called tunneling nanotubes. The Texas A&M approach amplifies that natural power-sharing system without changing genes or adding traditional drugs.

Therapies that aim to boost mitochondrial number with small molecules face a practical hurdle. Many compounds are flushed from cells within hours, which means frequent dosing. The larger nanoflowers behave differently. They are big enough to remain inside donor cells and continue to prod mitochondrial biogenesis for longer. The team suggests that could make any future therapy less burdensome to administer, perhaps on a monthly schedule rather than daily. That idea will need careful testing.

“This is an early but exciting step toward recharging aging tissues using their own biological machinery,” Gaharwar said. “If we can safely boost this natural power sharing system, it could one day help slow or even reverse some effects of cellular aging.”

What was shown and what was not

The new study was done in human cells under controlled lab conditions. The researchers did not test the method in animals or people. That matters, because intercellular handoffs can behave differently in complex tissues. Safety questions also loom. Molybdenum disulfide is being explored for biomedical use, but any implanted material will demand rigorous toxicology and tracking. The team did not report off-target effects such as abnormal growth signals or unwanted survival of cells that should be cleared.

Still, the targets are compelling. Mitochondrial decline is implicated in heart failure, neurodegenerative disease, and the long tail of chemotherapy toxicity. If the transfer can be directed, it could support tissues that are otherwise hard to treat.

“You could put the cells anywhere in the patient,” Soukar said, noting the approach might be adaptable to different organs if delivery challenges can be solved.

What comes next

Moving from a Petri dish to a therapy will require answers on several fronts. Researchers will need to map how long the nanoflowers keep donor cells in a high-output mode and whether repeated administrations are safe. They will need a delivery method that gets donor cells near the right targets without provoking the immune system. And they will need to learn whether rejuvenated mitochondria persist and integrate or whether the effect fades as cells turn over.

There are also questions of equity and scale. Manufacturing consistent batches of donor cells and nanoscale materials is expensive. The team’s method relies on a phenomenon that cells already use, which may reduce the need for complex genetic engineering, but it will still face the realities of biomanufacturing, quality control, and cost.

The work arrives as the broader field of mitochondrial medicine matures. Separate lines of research are testing mitochondrial transfer as a way to blunt injury after heart attack, to rescue neurons under stress, and to restore muscle function in rare genetic diseases. The Texas A&M study adds a potentially generalizable boost mechanism that could make cell to cell transfers far more efficient.

An idea with reach, and boundaries

The phrase cell rejuvenation can invite hyperbole. The data here are specific. In cultured human cells, donor mitochondria restored energy levels and reduced cell death after acute insults. That is meaningful, and it is not immortality. The genome still ages. Telomeres still shorten. Cells accumulate damage outside the mitochondria. Any clinical use will likely be targeted, for instance to rescue heart muscle after chemotherapy or to strengthen fragile tissues that are failing early.

For now, the promise is in the mechanism. If you can reliably swap out depleted power units for fresh ones, you may stabilize tissues long enough for the body to heal. You may also learn when not to try, for example in contexts where prolonged survival of damaged cells would cause harm.

“By increasing the number of mitochondria inside donor cells, we can help aging or damaged cells regain their vitality,” Gaharwar said in the university’s announcement, describing a potential that will need careful guardrails as research proceeds.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Welch Foundation, the Department of Defense, and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, with additional backing from Texas A&M programs. That mix reflects the breadth of interest in interventions that keep cells powered. Energy may not be the only story in aging, but biology makes a strong case that it is one of the first chapters.