A surprise drop in Austin revived a 2004 anthem and reopened an old, thorny story about sampling, credit, and what it means to be defined by a single song.

A shock return for a song its creator sidelined

Near the end of a recent set at The Concourse Project in Austin, a chorus drifted over the room that thousands of club nights have baked into collective muscle memory. Call on me, call on me. For a moment there was disbelief, then a surge. Eric Prydz, who spent the better part of two decades avoiding the song that made him globally famous, had brought Call On Me back.

For years, the Swedish producer who built an entire modern touring vocabulary with immersive HOLO shows and meticulous progressive epics all but pretended the song did not exist. Fans knew why. Call On Me was a phenomenon, then a weight, a thing he could not control. Bringing it back was more than a crowd-pleasing gesture. It was an inflection point in a story that began long before the track topped charts and ignited an aerobics craze on living room TVs.

From a 1982 chorus to a 2004 juggernaut

Call On Me is inseparable from Valerie, the Steve Winwood single co-written with Will Jennings and first released in 1982. Rather than lift the original master, the 2004 club track was built around newly recorded Winwood vocals, a decision that connected Prydz’s single directly to the source while easing a path through the maze of sample clearance. The new recording also let the voice sit cleanly inside the sleek, looping architecture of big-room house.

The result was instant. Call On Me went to number one in the United Kingdom and ruled airwaves and dance floors across Europe. It belonged to that era when a simple, repeatable hook could move from dusk to dawn, from provincial superclubs to daytime radio, without losing power. The lyrics promised uncomplicated solace. The production did not clutter the offer.

The prehistory in the clubs

Like many hits in dance music, Call On Me did not begin as a formal studio project. In the early 2000s, French duo Together, a collaboration between Thomas Bangalter of Daft Punk and producer DJ Falcon, worked a Valerie-based loop into their DJ sets. In the booth it was a tool, not a track, something designed to lift a room for a few minutes before giving way to the next record. Word of its impact spread through the usual circuits of the time, pre-streaming and still reliant on white labels, bootlegs, and the authority of a room full of bodies.

That underground life blended into industry interest. When the version that the public eventually heard arrived under Prydz’s name, Together were not credited, a detail that has animated debate ever since. Ask around and you will hear different versions of the same story, filtered through memory and contract law. What is clear is that a live edit that once belonged to a few became a single that belonged to the world, now anchored to Winwood’s freshly recorded vocal and a polished, radio-ready structure.

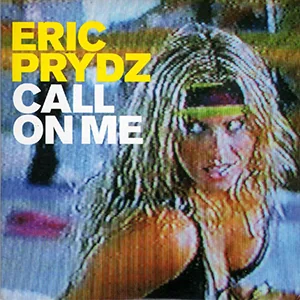

A music video that defined a moment

If the hook made the song in clubs, the video made it unmissable everywhere else. Shot in a London dance studio, it staged a high-gloss, tongue-in-cheek aerobics class led by dancer Deanne Berry, all headbands, hip pops, and knowing glances. The concept nodded to the gym montages of the 1985 film Perfect, a John Travolta and Jamie Lee Curtis artifact that practically begged to be parodied two decades later.

Broadcasters trimmed and rescheduled the clip for obvious reasons, which only added to its notoriety. The track was already a hit. The video turned it into an emblem of a mid-2000s moment when dance-pop gleefully courted excess and television still had the power to turn a song into an event by playing it every hour.

Why the star moved on

For Prydz, the same ubiquity that minted a career also threatened to flatten it. He relocated his creative identity toward long-form, slow-burning arrangements under his own name and heavier, techno-leaning material as Cirez D. Onstage he built cathedrals of light and geometry where tension was the point, patience the reward, and easy singalongs the exception.

In that world, dropping Call On Me would have felt like ripping a page from a yearbook in the middle of a symphony. So he did not. Over time, the refusal turned into lore. New fans found him through later anthems like Opus and through the spectacle of HOLO, never seeing the song that made all of this possible. Older fans accepted, even admired, the creative boundary.

The credit question that never quite settles

Dance music often blurs authorship. Tools become tracks, a functional loop turns into a hook that sells a million copies, and the energy of a scene condenses into a file that the rest of the world can buy for 99 cents. Call On Me sits squarely in that gray space. Together popularized a live edit based on Valerie. Prydz delivered the studio single that crossed over. Winwood and Jennings, as songwriters of the original chorus, are central to the credits and the royalties the track generates.

Another point sits in the background. Having a legacy artist re-record a vocal or a riff is common in sample-based music, because it simplifies licensing and gives producers a cleaner stem to work with. It is also a tacit handshake between eras, a way of saying that the new track does not just borrow, it collaborates. In this case, the handshake was literal, Winwood’s voice newly captured for a 21st century club record.

Back to where the chorus lands now

Which brings the story back to that room in Austin and to the reason the moment felt bigger than a surprise encore. When the chorus finally arrived, it did not erase the history. It braided it together. The 1982 melody stepped over the long-running credit arguments. The 2004 video that burned into adolescent brains receded, replaced by the sight of a modern crowd hearing a familiar thing in an unfamiliar context.

Artists cannot always choose the song that follows them, but they can decide how to live with it. By letting Call On Me back in, Prydz did not change what the track has meant to him, or to anyone who fell for the aerobics joke or the cleanly cut hook. He did something simpler. He let a room feel why the record worked in the first place, then moved on to the next build, the next drop, the next piece of his career that he can fully claim as his own.