In the autumn of 23 CE, as rebels surged into the imperial capital of Chang’an, the emperor who had promised to rebuild China on ancient lines waited inside Weiyang Palace. Outside, the Yellow River had already redrawn the map with catastrophic floods, coins of bewildering new shapes clinked uselessly in markets, and armies loyal to dynastic restoration closed in. Within hours, Wang Mang, a Confucian classicist who had made himself emperor, would be dead, his short-lived Xin dynasty overrun.

The classicist who became king

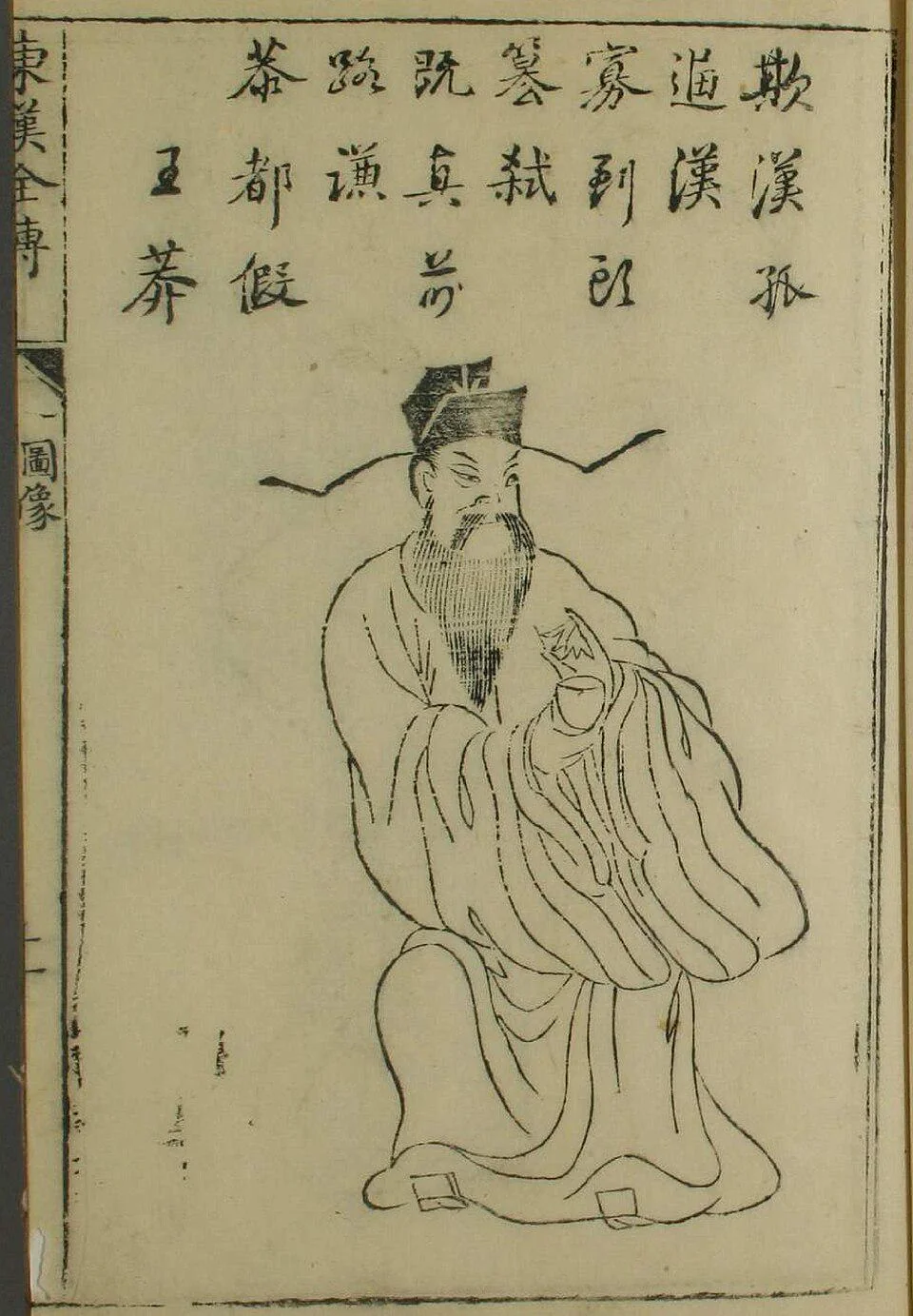

Wang Mang did not begin as a conqueror. Born in 45 BCE into a prominent but not imperial branch of the ruling clan, he was known first for austere habits and a devotion to the Confucian canon. In the twilight years of the Western Han, when court politics turned febrile, he proved tireless, pious and useful. He cultivated an image of rectitude so carefully that even his critics conceded his personal discipline.

That reputation carried him into the highest office. After the death of Emperor Ai, Wang Mang maneuvered to become regent for a child sovereign. When the boy emperor died, he arranged for an even younger heir and kept the reins as acting emperor. In 9 CE he took the final step, claiming that Heaven had shifted its favor and proclaiming a new dynasty. He called it Xin, meaning New.

The big idea: govern by the ancient books

Wang Mang looked backward to move forward. He believed that the golden age described in the classics could be recovered if government returned to first principles. It was less revolution than restoration as he conceived it, an effort to legislate what texts said a just order looked like. He restructured the bureaucratic hierarchy, restored archaic titles, and even renamed places and offices to match antiquity. Edicts cited omen reports and ritual precedents, as if history itself could be made to align through careful attention to words and rites.

The most dramatic measures targeted land and labor. He declared that all land was ultimately royal property and sought to revive the ancient well-field ideal, a nine-square grid in which families farmed individual plots while tending a central communal field that supplied taxes. He tried to cap private holdings and forbid the sale of land, which had increasingly concentrated in the hands of great families. He also moved against private slavery and the slave trade, limiting the sale of people to penal cases and seeking to convert many enslaved laborers into taxable commoners.

On money and markets, he pursued restoration with equal zeal. Between 9 and 14 CE the Xin court issued a carousel of new currencies, including knife and spade-shaped coins echoing bygone forms. At one point more than two dozen denominations circulated. The administration also announced new taxes and attempted to tighten control over key commodities. On paper it was a comprehensive program of moral economy. In practice, it was chaos.

Good intentions, hard edges

Many of Wang Mang’s aims resonated with long-standing problems. By the late Western Han, vast estates shielded by privilege had eroded the tax base. Peasants trapped in debt cycles slid into dependence as their land was swallowed by creditors. A state that drew revenue mainly from land struggled as taxable acreage shrank. Wang Mang was not wrong to see structural rot.

The difficulty was doing something about it while keeping the state standing. Confiscating elite land and curbing privileges required the cooperation of the very officials who enjoyed those privileges. They controlled local records, enforced edicts and collected taxes. They also knew how to stall. As orders filtered down, local administrators complied selectively or simply waited while turmoil elsewhere provided cover. Confusion over new coinage encouraged counterfeiting. Merchants and landlords found loopholes. Ordinary farmers faced rules that changed faster than the harvest.

Ritual antiquarianism could become a governing style. The court poured energy into determining correct forms and auspicious names, while the machinery of implementation lagged. The more Wang Mang invoked omens and precedents, the more his critics dismissed him as a bookish usurper rearranging labels while the frontier burned.

Then the river moved

Nature turned a policy crisis into a catastrophe. In 11 CE, the Yellow River burst its levees. It carved a new course and drowned broad swaths of the North China Plain. Farmland vanished under water. Millions were displaced. Famine followed. In the east, hungry bands coalesced into insurgent movements, one of them known for painting their eyebrows red. Along the northwest frontier, nomadic confederations tested a distracted government. The Xin state raised armies and requisitioned grain, but logistics faltered and loyalty wavered.

It became a race between reform and collapse. Wang Mang appointed new commanders, issued fresh currency regulations, revised land laws yet again. Each adjustment acknowledged that previous decrees had failed to take root. Each also signaled weakness. The more the center tinkered, the more local actors hedged their bets, waiting to see which banner would fly over Chang’an by year’s end.

The fall of Xin

In the summer of 23 CE, a Han restoration faction gathered momentum in the east. At Kunyang, forces rallying under the Han name won a stunning victory against a much larger Xin army. News ricocheted through the provinces. Garrisons capitulated. Allies defected. By the time rebel columns reached Chang’an, the New Dynasty was a shell sustained by proclamation and palace guard.

Wang Mang refused to flee. Accounts from the official histories describe a last stand inside Weiyang Palace as insurgents scaled the walls. He was killed in the fighting. The Xin experiment had lasted fourteen years. Within two more, Liu Xiu, a scion of the old imperial clan and a skilled commander who rose in the turmoil, would reunify much of the realm as Emperor Guangwu and found the Eastern Han.

A legacy argued across two millennia

Was Wang Mang an idealist who tried to correct long-term injustices and was overwhelmed by disaster, or a calculating usurper who cloaked ambition in antique robes? The sources that survive were compiled under Han successors who had every reason to brand him a villain. They preserve details that can be checked against archaeology and economic evidence, but their judgments are framed by a politics of legitimacy.

Modern historians have picked at that framing. The outlines are clear enough. He borrowed the moral authority of the classics to justify sweeping interventions. He challenged entrenched interests that hollowed out the late Western Han. He underestimated the practical obstacles of implementation and the capacity of local elites to resist without open revolt. He also faced a cascade of environmental shocks that would have strained any regime.

What remains most striking is the ambition. The land program attempted to redefine property by law. The slave regulations tried to expand the ranks of free commoners. The currency changes sought to yoke exchange to a moral order rather than market convenience. None of it looked like modern egalitarianism. It was a conservative revolution, an effort to revive an imagined past to fix a troubled present.

In the end, Wang Mang could not conjure the classical age he revered. Laws without enforcement bred cynicism. Ritual without results bred anger. Floods and hunger converted discontent into rebellion. When his palace fell, so did the idea that a lost golden age could be written back into being by decree. Yet the problems he tried to solve did not disappear. Later dynasties would conduct their own redistributions, revise tax rolls and wrestle again with the concentration of land and privilege.

That is one measure of his significance. Wang Mang’s reign is short and often caricatured, but it sits at a hinge in Chinese history, between the first Han and the second, between an ideal of order drawn from ancient texts and the stubborn realities of governance. He offers a caution that still travels well. Grand designs are not enough. The country outside the palace has to recognize itself in the laws, or the laws will not hold.