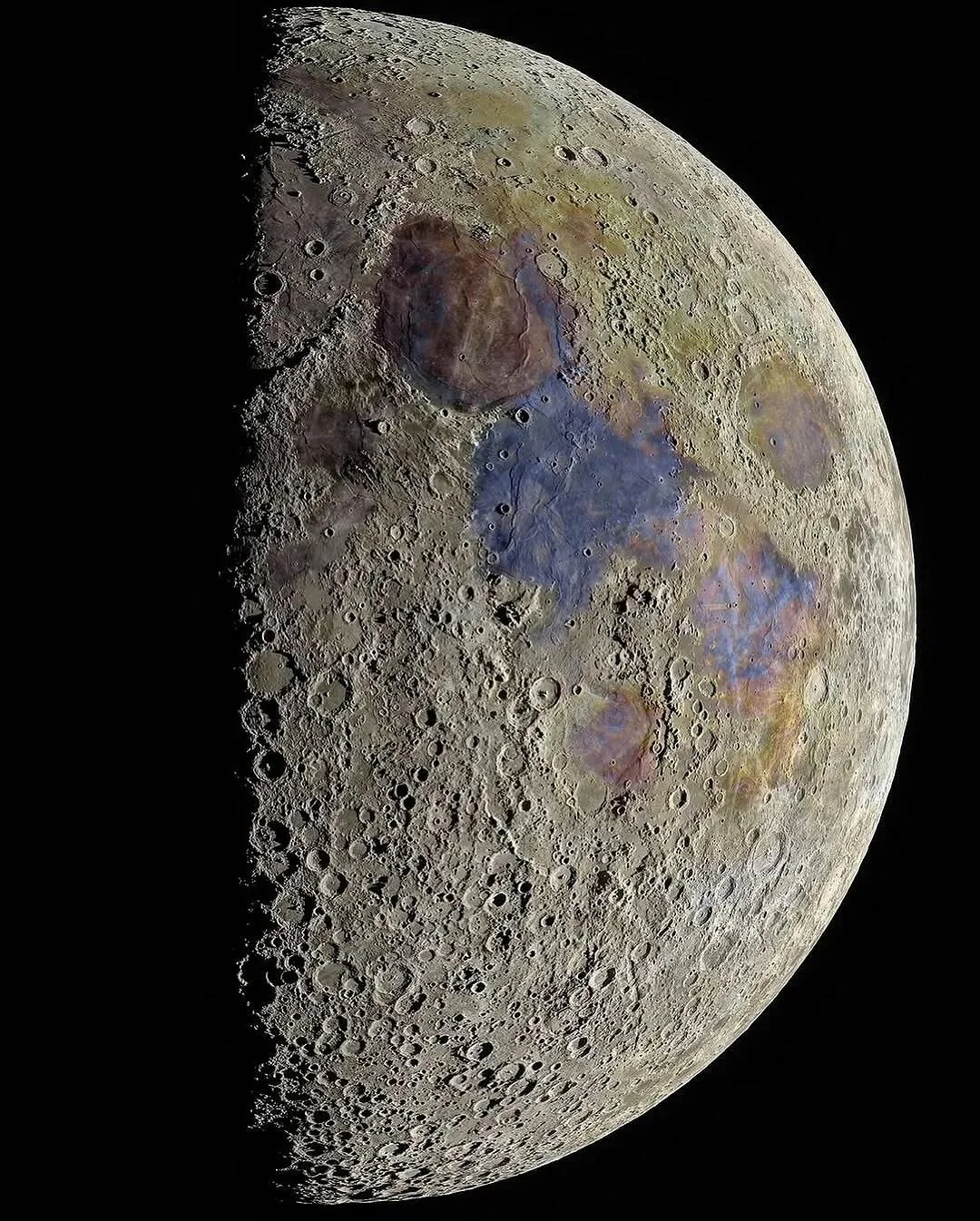

You think you know the Moon until a billion-plus pixels stare back. In Andrew McCarthy’s colossal 1.3-gigapixel mosaic, every wrinkle, ripple, and ray basin leaps into view, revealing a world both battered and breathtaking. It is the kind of image that turns casual glances into long, quiet study.

Built from more than 280,000 individual frames, the portrait invites the public to roam a familiar face with unfamiliar freedom. What looks at first like a single snapshot is, in fact, a feat of patience, precision, and atmospheric negotiation.

A Moon reimagined at gigapixel scale

McCarthy, a renowned astrophotographer, set out to assemble a lunar view that rewards deep exploration. The result is a sprawling mosaic where the smallest visible features measure on the order of hundreds of meters across, pushing the limits of what a ground-based telescope can resolve through Earth’s restless air.

Instead of one long exposure, he recorded torrents of short video frames across the Moon’s disk, then extracted the sharpest slivers from each. The technique, known as lucky imaging, freezes brief moments of atmospheric steadiness. Stacking and sharpening those moments across thousands of tiles yields a coherent, crisp whole.

A backyard telescope, industrial-scale data

Creating a lunar portrait at this scale is less a single click and more a marathon of micro-decisions. Each tile requires careful focus, exposure adjustment, and alignment. The project demands not just clear skies but consistent skies, so that contrast, noise, and seeing conditions match well enough to stitch without visible seams.

On the back end, the workload is staggering. Terabytes of data pass through stacking software, wavelet sharpening, and deconvolution, followed by a meticulous mosaic process to ensure craters, rilles, and mountain rims line up true. The labor shows in the final product: relief looks tactile, ejecta rays stretch like frost across the mare, and delicate wrinkle ridges thread the basalt plains.

The science hidden in lunar color

One of the image’s most striking qualities is its color. The palette is not a filter for drama; it is a scientific flourish. McCarthy enhances subtle chromatic differences already present in the Moon’s reflected light, revealing variations tied to mineral content and geologic history.

The darker seas, or maria, are ancient lava flows rich in iron and titanium. Some regions skew bluish where titanium is higher; others trend toward rusty brown. The bright highlands, dominated by aluminum-rich feldspar, take on pale, warm hues. Color, here, is a map of the Moon’s chemistry, not a painter’s invention.

Can you see the Apollo landing sites?

Short answer: not directly in a ground-based photograph, even one this sharp. From Earth, typical atmospheric seeing blurs details to around one arcsecond or more, which at the Moon translates to roughly two kilometers. Lucky imaging and large apertures can beat that, tightening effective resolution to a few tenths of an arcsecond, or a few hundred meters on the lunar surface.

The Apollo artifacts are far smaller. Lunar module descent stages are a few meters across, and astronaut tracks a fraction of that. Those features are visible from orbit, thanks to NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO). The LRO Narrow Angle Camera images reach about 0.5 meters per pixel, enough to show the descent stages, instrument packages, and the trails astronauts wore into the regolith.

What McCarthy’s mosaic can do is guide viewers to the regions that made history: the tranquil expanse of Mare Tranquillitatis for Apollo 11, the Ocean of Storms for Apollo 12, the Fra Mauro and Descartes highlands, Taurus-Littrow’s rough valley. It offers the sweeping context that completes the close-ups from orbit.

Reading the Moon’s scars

Spend time wandering the image and patterns emerge. The lunar near side is a study in contrast: glassy, dark basalt basins punctured by bright, hard highlands scarred with a fractal population of craters. Central peaks stand in some bowls like rebounding splashes frozen in rock, reminders that impacts behave like high-energy fluid events at planetary scales.

Look for crater rays that radiate like spokes from bright, young impacts such as Tycho and Copernicus. Notice how older features soften and smear under the pelting of micrometeoroids and the subtle churn of thermal cycling. On the Moon, there is no weather, but there is time, and time alone does the work.

Why this image matters now

Ultra-high-resolution images like McCarthy’s underscore how far citizen astrophotography has come. With patience, skill, and carefully chosen equipment, a dedicated individual can produce a scientifically meaningful view that complements professional datasets. The mosaic is not a replacement for orbital imaging; it is a bridge, connecting a backyard vantage to the frontier of exploration.

That bridge matters as humans prepare to return to the Moon. Artemis missions are rekindling public attention, and resources such as NASA’s LRO QuickMap allow anyone to dive into petabytes of orbital data. A gigapixel ground view meets that orbital atlas in the middle, grounding precise measurements in a sweeping, intuitive portrait.

There is also educational power here. A classroom can use the mosaic to practice reading impact stratigraphy, to trace the boundaries of Mare Imbrium, to connect color to composition. Teachers can place the Apollo regions in their broader geologic neighborhoods and discuss why landing sites were chosen for safety, science, and engineering constraints.

The craft behind the clarity

To reach this level of detail, every step matters. Focusing to the limit of diffraction, matching camera gain to the seeing, capturing at high frame rates to freeze turbulence, and keeping optics thermally stable all stack the odds in favor of sharpness. The final tuning is equal parts art and restraint: enough sharpening to reveal, not so much that processing artifacts masquerade as geology.

The scale of the mosaic also means the imperfections of our own atmosphere become part of the story. The Moon never climbs as high as stars near the zenith, and observations pass through thick wedges of air that shimmer with temperature gradients. Lucky imaging turns that foe into an occasional friend, snatching clarity from fleeting stillness.

How to explore it like a geologist

Start with the basins. Trace Mare Serenitatis and Mare Tranquillitatis, then follow the sinuous rilles that wind like dried riverbeds, vestiges of lava channels. Find the Apennine Mountains arcing along the edge of Mare Imbrium, their foothills littered with secondary craters.

Next, hunt for color contrasts at basin edges where highland materials drape onto basalt. Look for dark-halo craters that punched through pale highlands into buried darker rocks. Use the rays as timelines: the brighter and crisper the ray, the younger the impact.