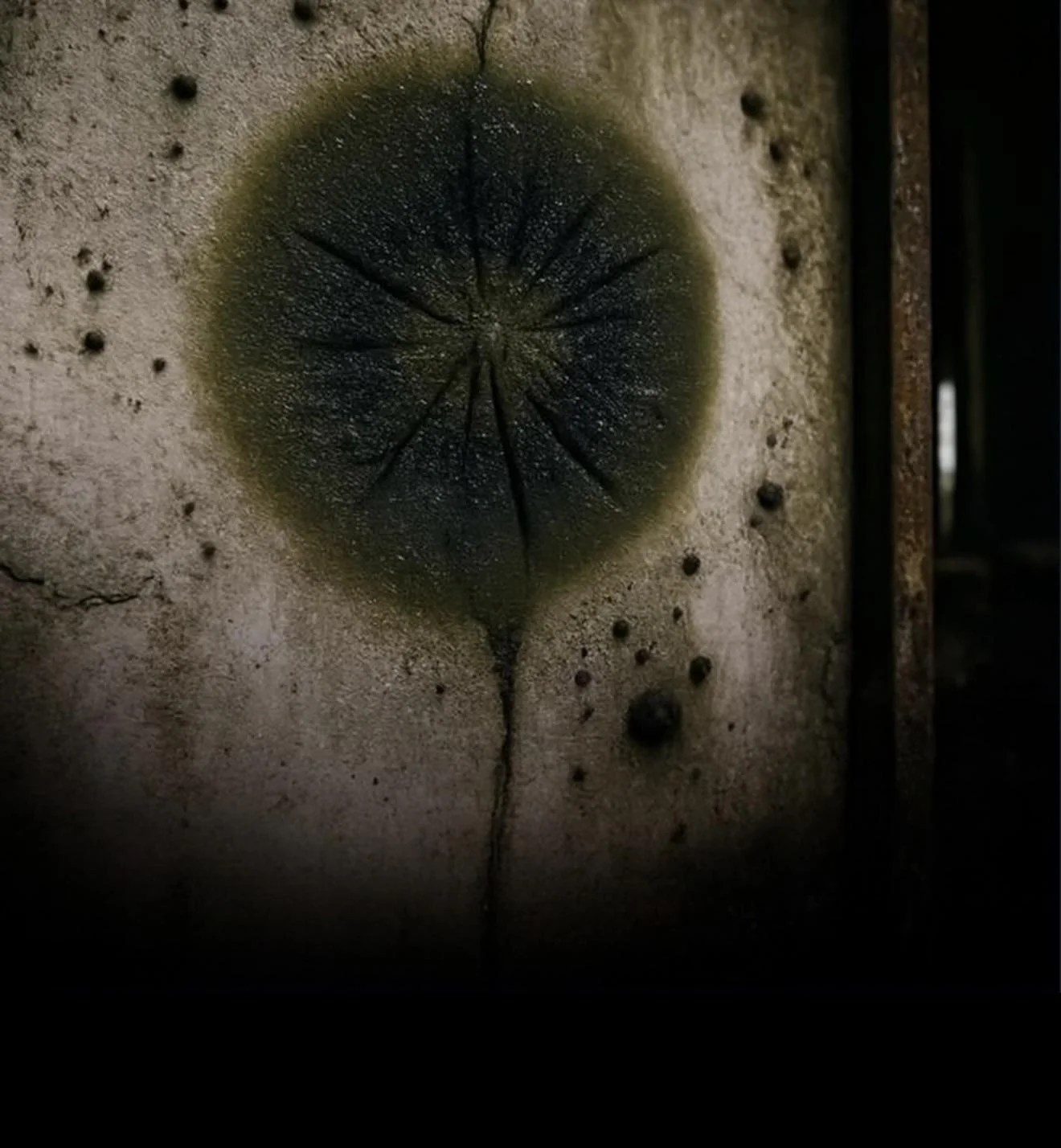

In the shadow of Chernobyl’s ruined reactor, something black and stubborn has taken hold. Clinging to concrete and steel where the radiation would fell most living things, these fungi are forcing scientists to reconsider what it means to make a living.

The question no longer sounds like pure science fiction: can some organisms use radiation the way plants use light?

What scientists found at Chernobyl

In the years after the 1986 disaster, microbiologists cataloged an unexpected community inside the reactor buildings and across the exclusion zone. Many of the newcomers were darkly pigmented, or melanized, fungi. Teams led by Ukrainian mycologist Nelli Zhdanova reported that several species not only tolerated intense radiation but actually oriented their growth toward radioactive sources, a behavior they called radiotropism.

In lab tests, spores and threadlike hyphae of species including Cladosporium sphaerospermum turned toward collimated beams of beta and gamma radiation, even when no extra nutrients were placed near the source. The researchers ruled out simple attraction to carbon or other chemicals in the setup. Something about the radiation field itself seemed to be drawing the fungi in.

Similar melanized species have popped up in other charged environments, including the pitch-black cooling pools of working nuclear reactors. In those pools the water can visibly darken when fungal colonies bloom. Melanin, the same family of pigments that colors human skin and hair, is common among these organisms and appears to be more than mere sunscreen.

How melanin might make a meal of radiation

At the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, microbiologist Ekaterina Dadachova and immunologist Arturo Casadevall set out to probe melanin’s role. In peer-reviewed experiments, they exposed melanized fungi to radiation levels hundreds of times above background under nutrient-limited conditions. Compared with nonmelanized mutants, the darkly pigmented cells grew faster and accumulated more biomass.

The team found that melanin’s electronic behavior changed under ionizing radiation, boosting its ability to shuttle electrons. Electron transfer is the backbone of energy capture in biology, from photosynthesis to respiration, so a pigment that turns radiation into a livelier electron economy could in theory help power growth.

“Irradiated melanin manifested a 4-fold increase in its capacity to reduce NADH relative to non-irradiated melanin.”

Ekaterina Dadachova and colleagues, PLoS One, 2007

In the same study, melanized cells of Cladosporium sphaerospermum and other fungi exposed to high radiation produced more colonies and incorporated carbon at higher rates than their nonmelanized counterparts. The result does not prove that radiation is the sole energy source, but it points to melanin as an energy transducer that may help organisms tap radiation to stretch scarce nutrients further.

Radiosynthesis, still a hypothesis

Scientists often describe the proposed process as radiosynthesis, by analogy to photosynthesis and chemosynthesis. The label captures the intrigue but not the unresolved details. No step-by-step metabolic pathway has been mapped from gamma rays to ATP to built tissue. It remains possible that radiation alters melanin in ways that make the fungi more efficient at using conventional food rather than literally eating radiation.

“The discovery of melanized organisms in high radiation environments … combined with the phenomenon of radiotropism raises the tantalizing possibility that melanins have functions analogous to other energy harvesting pigments such as chlorophylls.”

Ekaterina Dadachova and Arturo Casadevall, Current Opinion in Microbiology, 2008

Subsequent work has added threads, if not yet a completed tapestry. A 2022 study in Scientific Reports tracked how gamma and ultraviolet radiation changed growth and pigmentation in two fungal species, indicating that radiation can nudge fungal metabolism and melanin production. The findings enrich the picture of a complex stress response that may include energy capture, protection from free radicals, and adaptive shifts in gene expression.

From disaster zones to orbit

Fungi do not stop at terrestrial ruins. Surveys of the International Space Station have repeatedly found hardy microbial communities on surfaces and in air samples, and many of the resident fungi are pigmented. Radiation levels in low Earth orbit are far above those on the ground, yet the station’s dark molds persist, suggesting that melanin helps them handle cosmic rays as well as reactor emissions.

In 2018 and 2019, researchers tested Cladosporium sphaerospermum on the station to see whether a thin living layer could attenuate ionizing radiation. The preprint report described modest shielding effects that increased as the fungus grew, hinting at bio-based materials that could protect equipment or even crew on deep-space missions. The work was preliminary, and it awaits independent replication and peer review, but it fed serious conversations about blending biology and engineering to solve one of spaceflight’s hardest problems.

What it could mean for people

For nuclear cleanup on Earth, radiotrophic fungi are unlikely to be silver bullets. They do not neutralize radioactive isotopes. What they can do is influence how radiation interacts with materials and potentially sequester certain metals through chemical binding. Their pigments could inspire new radiation shields made from melanin composites, which early studies suggest can block ionizing radiation more effectively per unit mass than many traditional materials.

There are bolder ideas on the horizon. Some researchers have proposed building self-replenishing barriers that grow from spores, water, and nutrients, thickening in response to a radiation gradient. Others speculate about bioelectric devices that harness melanin’s electron-shuttling behavior to harvest a trickle of energy from radiation-rich environments. These concepts sit at the boundary of science and engineering, where a better mechanistic understanding will make or break them.

The scientific debate, in plain view

Claims that fungi at Chernobyl truly feed on radiation can overshoot the data. The field is young, the experiments are hard, and alternative explanations remain on the table. The strongest evidence shows that melanized fungi change their growth and metabolism in radiation fields and that melanin’s electronic properties shift in ways that could support energy transduction. The decisive test would trace energy from ionizing radiation into biochemical currency and new biomass under rigorously controlled, nutrient-limited conditions.

That is why ongoing work matters. Research plans presented to the Committee on Space Research in 2022 outlined future studies at the Chernobyl site that will measure how radiation exposure alters metabolism in melanized fungi such as Cryptococcus neoformans. The tools are catching up, from high-resolution spectroscopy of pigments to isotope tracing of carbon fixation. With each experiment, the picture sharpens.