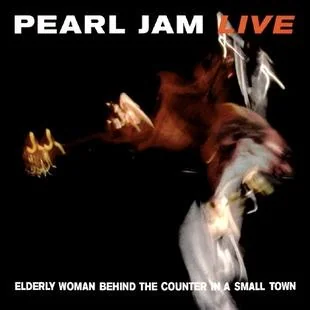

It is one of the most tender songs in Pearl Jam’s catalog, yet it begins with a mouthful: a title that reads like a short story. “Elderly Woman Behind the Counter in a Small Town” landed on the band’s 1993 album Vs. with a wink—and a purpose. In an era when their track lists leaned spare and blunt, the band chose a name that lingered, just like the life it portrays.

A small-town epic hiding in a title

On record, the song is modest: an acoustic strum, a midtempo sway, a voice testing the edges of memory. Its narrator, stuck where time has stalled, recognizes a face from the past and confronts what years of inertia can do to a person. In a band renowned for cathartic roars, this is a quiet reckoning, all sighs and sidelong glances.

The title does unusual lifting. It sketches a stage—counter, town, age—before a single lyric arrives, inviting listeners to picture fluorescent lights and linoleum floors, the hum of a soda cooler, the polite exchanges that buffer deeper regret. Pearl Jam didn’t just name a track; they framed a scene.

When Pearl Jam zigged on song titles

By the early 1990s, Pearl Jam’s discography was dotted with one-word thunderbolts. On Ten and the bulk of Vs., the band gravitated to blunt nouns and commands, fit for radio buttons and CD spines. The aesthetic felt of a piece with the era: concise, heavy, immediate.

The one-word streak that set up the punchline

- Ten (1991): Alive, Black, Jeremy, Release, Deep, Garden, Porch, Oceans

- Vs. (1993): Go, Animal, Daughter, Dissident, Blood, Rats, Leash, Indifference

In that context, “Elderly Woman Behind the Counter in a Small Town” reads like a deliberate zag—a tongue-in-cheek counterweight to the band’s own habit. The name sprawls, as if to say: not everything that matters can be reduced to a single word. It plays against the grain of grunge’s terseness and signals a story with air and empathy in it.

There was a practical side, too. In set lists and on radio, the song was quickly shortened to “Elderly Woman” or, in fan shorthand, “Elderly Woman…”. The edit made it more manageable without dulling the point; the original title still loomed in the liner notes like a narrative prologue.

How long titles shape how we listen

Long names have a history of telegraphing intent. They can be punch lines, provocation, or promise. In rock and pop, they often cue a story before a sound: a message that the artist is chasing mood over minimalism, specificity over slogan.

Pink Floyd toyed with this in late-1960s psychedelia with “Several Species of Small Furry Animals Gathered Together in a Cave and Grooving With a Pict,” a prankish title that doubles as a dare. Primitive Radio Gods tipped a noir hand in the 1990s with “Standing Outside a Broken Phone Booth With Money in My Hand,” a name that feels like a cinematic establishing shot. A decade later, bands like Fall Out Boy and Panic! at the Disco made verbose titles a pop-punk badge of wit and self-awareness.

Sometimes the lengths are personal, even defiant. Fiona Apple’s second album became famous for a poem-length title born of frustration with press narrative. As she told The Washington Post, “It came from being made fun of,” a shrug turned artistic choice that wound up setting a Guinness-worthy mark. The point, in each case, is control: if a headline is going to follow you, write it yourself.

It came from being made fun of.

That same impulse—taking charge of the frame—ripples through Pearl Jam’s choice. For a band often reluctant about the machinery of fame, a title that reads like a diary note rather than a marketing line feels apt. It resists the easy tag, nudging listeners to meet the song on its own terms.

A softer lens in the grunge glare

Part of the title’s staying power is how neatly it matches the music’s perspective. The verses dwell on recognition and regret, on the shelfed dreams of someone who never left the town lines. It’s a story about how the past can elbow into the present without warning—and how pride, fear, and love tie knots around the simplest hello.

Within Vs., a record that opens with the ferocious “Go” and the snarling “Animal,” this track stands out precisely because it exudes patience. The guitars breathe. The melody leans on vowel sounds and pauses. Even the chorus feels like someone trying to speak through a lump in the throat. The novelistic title primes the ear for character and place; the song delivers both, in miniature.

Metadata, marketing, and the myth of the perfect title length

For decades, practical considerations nudged artists toward brevity. Vinyl labels, CD trays, and radio playlists all reward short, punchy names. The 1990s squeezed titles onto jewel-case spines; the 2000s funneled them into MP3 tags and tiny LCD screens. In that environment, Pearl Jam’s decision reads as a gentle bit of subversion.

Streaming has loosened those constraints. Today, a song called “I Know The End” sits comfortably alongside a track named “The Only Difference Between Martyrdom and Suicide Is Press Coverage.” Algorithms don’t run out of ink. But the underlying calculus remains human: titles are first impressions, and the best ones—long or short—promise a world worth entering.

The mouthful that stuck

Three decades on, “Elderly Woman Behind the Counter in a Small Town” is a set-list staple and a reliable singalong, proof that intimacy can carry a stadium. The title still makes people smile when they try to say it fast; it still prompts a quick abbreviation in scribbled notes. Yet it also continues to do what it did on release day—slow the listener down, sharpen the focus, pull the camera in close.

Pearl Jam never needed to chase novelty to make their songs endure. Here, they used the simplest trick in the book: tell listeners exactly where they are before the first chord rings out. The rest of the song fills in the faces and the feelings. Sometimes, the longest titles mark the smallest moments—and that is exactly why they last.