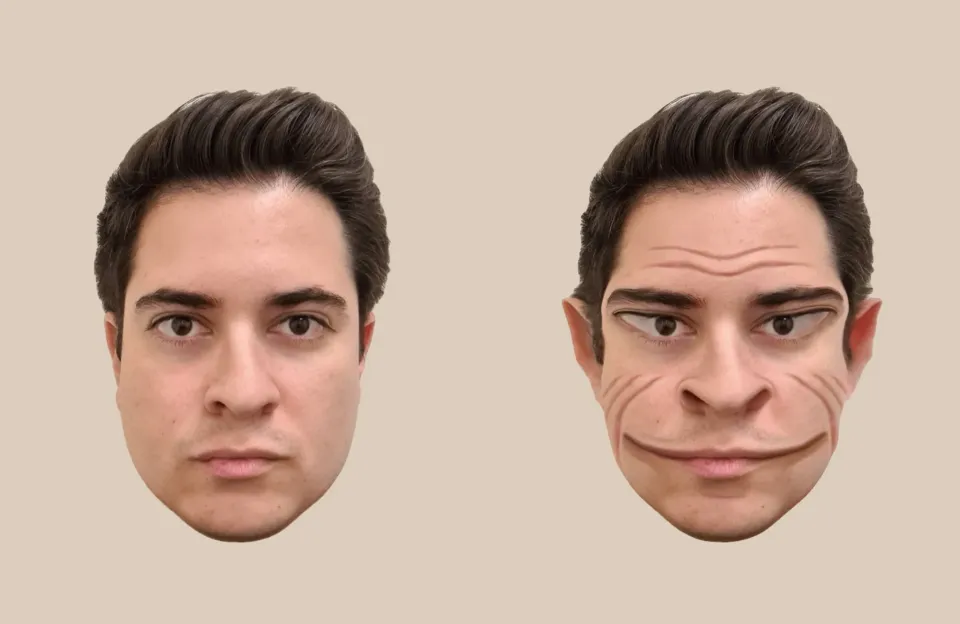

Stare at a tiny cross between two celebrity portraits, and within seconds their faces seem to buckle and warp into ghoulish caricatures. Eyes balloon, jaws stretch, noses twist—then snap back to normal the moment you look directly at them. The sensation is so visceral it can feel like a jump scare delivered by your own brain.

Psychologists call it the Flashed Face Distortion effect, and more than a decade after researchers first documented it, the illusion is surging through short-form videos and demos once again. Beyond the wow factor lies a revealing lesson about how vision works: the brain doesn’t passively record reality—it predicts, compares and exaggerates it on the fly.

What the illusion is—and how to see it

The basic recipe is simple. Two faces appear side by side while a fixation mark sits between them. As you lock your gaze on the mark, the portraits flash rapidly—typically several images per second—each aligned so the eyes land on the same horizontal line. Keep staring at the mark, and the faces in your peripheral vision seem to transform into grotesque, sometimes hilarious distortions. Shift your eyes to any face, and the effect collapses instantly.

This phenomenon was first reported in 2011 by a team at the University of Queensland, including Matthew M. Thompson and Jason M. Tangen, who published their findings in the journal PLOS ONE. Their original demonstration, which quickly went viral at the time, showed how ordinary portraits turn monstrous when viewed in rapid alternation at the edges of our visual field.

Try it safely

- Sit an arm’s length from your screen. If you are sensitive to flashing images or have a history of photosensitive epilepsy, skip this exercise.

- Play a demo video that places a fixation cross between two portraits. A classic example is the 2011 demonstration archived on YouTube (search: “Shocking illusion – Pretty celebrities turn ugly!”).

- Keep your eyes glued to the cross; resist the urge to glance at the faces.

- Notice how features balloon or shrink, how asymmetries amplify, and how expressions appear to melt or harden. Now look directly at a distorted face—poof, it’s normal.

Why your brain conjures “monsters” from ordinary faces

To understand the effect, it helps to remember that peripheral vision prioritizes speed and change over detail. When faces flicker quickly at the edges of our gaze, the visual system emphasizes the differences between successive images—an efficient way to detect what matters in a dynamic scene. In the Flashed Face Distortion effect, that efficiency becomes a bug and a feature: the brain enhances contrasts between facial features from one frame to the next, inflating what is big, shrinking what is small, and accentuating asymmetries.

Researchers propose several interacting mechanisms. Rapid alternation sets up sequential contrast and adaptation—after seeing wide-set eyes, the next pair appears even closer; after a broad chin, the next looks pinched. Because the images are aligned at the eyes, those comparisons lock in where the brain has high confidence, letting differences elsewhere appear more extreme. And since faces are a special category for the brain—processed by networks that include the fusiform face area—tiny deviations in shape and spacing can be amplified into dramatic percepts when detail is scarce.

The illusion also rhymes with classic effects like the Thatcher illusion, where upside-down faces look normal even when the eyes and mouth are inverted. In both cases, the visual system assumes a familiar template and can be led astray by context. With Flashed Face Distortion, the context is time: your brain is comparing a stream of faces and exaggerating contrasts to save computation.

From lab curiosity to viral staple

In the years since the Queensland team’s first publication, the effect has become a reliable crowd-pleaser, especially in video formats that can lock a viewer’s gaze with a central marker while cycling through a gallery of familiar faces. Contemporary creators often align portraits carefully and increase the pace to heighten the impact. The result is a perfect package for the attention economy: instant, surprising, and repeatable.

But the effect is more than a party trick. It has provided researchers with a tool to probe the limits of face perception. Because the distortion is so sensitive to timing, alignment, and peripheral viewing, it can be used to test how quickly the brain adapts to changes in complex stimuli, how contrast across time shapes perception, and how global templates for faces interact with local feature processing. Even the fact that the effect vanishes with a direct glance highlights how eye movements and fixation shape what we see—and what we think we see.

What the illusion reveals about perception

At its core, Flashed Face Distortion underlines a crucial fact: seeing is inference. The brain is constantly predicting the next moment and using differences between successive snapshots to update its model of the world. Most of the time that shortcut is adaptive. On a busy street, rapidly spotting what has changed—an approaching bicycle or a turning car—can be lifesaving. In a laboratory-style visual stream, that same strategy pushes differences into caricature.

It also shows how deeply context matters. The very same photograph can look ordinary or absurd depending solely on when and where you look at it. That should make us humble about our perceptual certainties. If an unedited face can morph into something monstrous within a stable, controlled setup, imagine how easily more ambiguous scenes can be misread in the wild.

There’s a creative flip side, too. Caricature artists and portrait photographers have long known that exaggerating a person’s most distinctive traits can make a likeness feel more “like” the subject. The illusion suggests why: our brains naturally code faces relative to one another, so distinctiveness is magnified by comparison. Digital artists experimenting with generative tools might find the effect a useful mental model—align features, iterate quickly, and let contrast do the work.

Limits, caveats, and the path ahead

The Flashed Face Distortion effect depends on careful staging. If the faces are not aligned at the eyes, if the flash rate is too slow or too fast, or if you can’t maintain fixation, the distortions weaken. Viewers’ experiences also vary; some see dramatic warping, others only subtle changes. And because the effect uses flashing sequences, creators should include warnings for those sensitive to strobing imagery.

Scientifically, the illusion has opened up questions rather than closed them. Which features drive the strongest distortions—eye spacing, mouth width, facial asymmetry? How does the effect scale with age or visual expertise? Can machine-vision systems trained on faces exhibit analogous time-based contrast effects, and if so, could that inform how we design more robust algorithms?

Those lines of inquiry connect a viral curiosity to larger debates in neuroscience and AI: we build models of the world, then we test them against change. Sometimes those tests make monsters. More often, they keep us oriented and safe.