A minute before Halifax exploded, a railway dispatcher leaned over a telegraph key and chose duty over survival. Patrick Vincent Coleman knew a burning munitions ship in the harbor would obliterate the waterfront. He tapped out a warning anyway.

The morning the harbor turned to fire

On December 6, 1917, Halifax woke to a low winter sun and the steady churn of a wartime port. Convoys gathered here during the First World War, and the Narrows—a tight channel between the city and Dartmouth—funneled ships in and out like a busy artery.

Just after 8:45 a.m., the French freighter Mont-Blanc, laden with thousands of tons of explosives, collided with the Norwegian relief ship Imo. Sparks and a torrent of benzol ignited the Mont-Blanc’s deck. The fire drew onlookers to the piers and windows, unaware that the ship’s cargo—TNT, picric acid, and guncotton—had turned the harbor into a bomb with a burning fuse.

A decision at the telegraph key

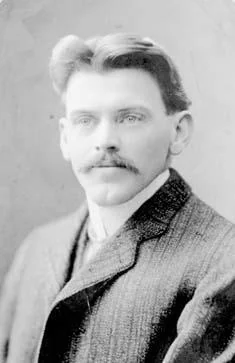

At the Intercolonial Railway’s Richmond station near the waterfront, 45-year-old dispatcher Vince Coleman weighed a terrible calculation. He and a colleague were warned to run. But an inbound morning passenger train was due, its cars filled with travelers who would be rolling straight into danger.

Coleman turned back to his post. He began hammering a message onto the telegraph circuit that linked stations up and down the line, knowing that seconds mattered and that the fireship could erupt at any moment. He sent a stop order for trains approaching the city and kept tapping.

“Hold up the train. Ammunition ship afire in harbour making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Good-bye, boys.”

Nova Scotia Archives preserves Coleman’s words, a fragment of calm procedure wrapped in grim clarity. It was the language of a professional who understood both the power of a signal and the cost of time.

The blast that erased a neighborhood

At 9:04 a.m., the Mont-Blanc detonated. A white flash tore across the harbor, then a shock wave pancaked houses, lifted trains from tracks, and splintered trees like matchsticks. A moment later, a towering wave heaved ashore, scouring the waterfront that the fire had just lured crowds to see.

Nearly 2,000 people were killed, about 9,000 injured, and more than 25,000 left without shelter. The Richmond district was pulverized. Windows shattered miles away; a plume of smoke roared into the sky. Night fell early as a snowstorm swept in, snuffing daylight and hampering rescue.

Historians including Janet Kitz and Laura MacDonald have chronicled the catastrophe’s anatomy—how a chain of small decisions and wartime pressures set two ships on a collision course, and how a city built for maritime enterprise suddenly found itself grappling with industrial-era destruction. It was, for a time, the largest human-made explosion the world had ever seen.

The trains that never arrived

Coleman’s signal rippled outward. The inbound passenger train halted outside the city, its cars spared the blast and the storm of debris that followed. Railway crews elsewhere braced, redirected traffic, and prepared to move doctors, nurses, and supplies as reports crackled in from shattered stations.

In the hours after the explosion, rail lines became lifelines. Trains ferried the injured to intact hospitals and carried relief workers into the city. The Intercolonial’s network, so often the quiet background of daily life, turned into the skeleton of the response. Coleman did not live to see it, but his last act bought precious time and kept hundreds out of harm’s way.

Aftershock, aid, and the work of memory

Halifax’s recovery began almost immediately, even as smoke still hung over the Narrows. Medical teams formed in streets. Neighbors dug with bare hands. From Boston—Halifax’s maritime counterpart—aid raced north overnight, a bond the province of Nova Scotia honors each December with the gift of a Christmas tree for Boston’s holiday display.

Rebuilding took years. Investigations mapped the tangle of maritime rules, pilotage decisions, and wartime practices that had failed the harbor. Out of the wreckage came reforms in shipping controls and port safety, along with a deeper public understanding of what an industrial supply chain could unleash when something went wrong.

The human legacy is held in names. At Fort Needham’s Halifax Explosion Memorial Bell Tower, the victims are listed, a roll call that stretches across families and neighborhoods. Coleman’s name is among them, and elsewhere in the city small plaques and street signs continue the story in the places where ordinary life resumed atop extraordinary loss.

Why this century-old signal still matters

Disasters are often framed by numbers, but they turn on moments. Coleman’s decision lives on because it compresses larger truths: that split-second choices matter; that training and duty shape instinct; that communication, in crisis, can be as life-saving as a tourniquet. He knew what a single message could do, and he sent it.

In the era of modern alerts and redundant systems, it is easy to assume the network will always catch us. The Halifax Explosion reminds us that systems begin with people. The clearest warning can come from one person at one desk who decides to act, even when the cost is personal and immediate.

Halifax rebuilt, and the harbor returned to work. The Narrows looks placid again, the city’s neighborhoods knit back together over a century of ordinary days. Yet every December, as bells toll and stories are retold, one signal breaks the silence: a few spare lines tapped out against time, a train that never arrived, and the enduring idea that courage is often a quiet act, performed with both eyes open.