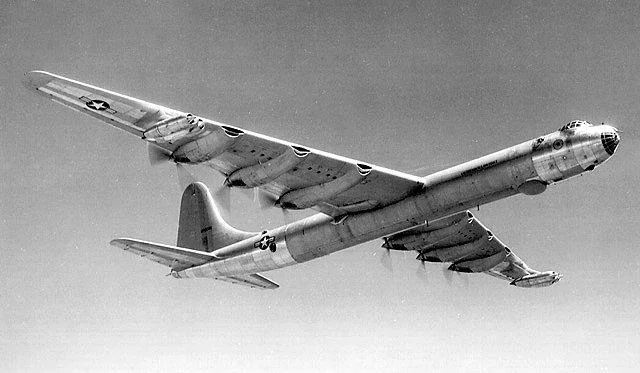

The airplane that once cast a shadow longer than a football field was born from a fear that Europe could fall and oceans might suddenly feel small. The Convair B-36 Peacemaker was an audacious answer: six piston engines pushing, four jet engines roaring, and a mission measured in thousands of miles and days, not hours. It was the largest combat aircraft ever to take to the skies—and for a crucial decade, it carried the United States’ nuclear deterrent on its colossal wings.

Conceived in crisis, built for distance

The B-36 began on the drafting tables in 1941, when U.S. planners asked a hard question: What if Britain fell and American bombers had to strike Europe and return without forward bases? The answer became an aircraft with a range of approximately 10,000 miles and a service ceiling above 40,000 feet, capable of leaping oceans and climbing over weather and defenses.

Though the war ended before the Peacemaker entered service, the Cold War arrived just in time to give it a defining role. The prototype first flew in 1946, and by 1948 the B-36 was operational with Strategic Air Command, its wings spanning 230 feet—still the longest wingspan of any combat aircraft ever built. Designed for an era of uncertainty, it emerged as the bridge between piston-powered giants and the jet-powered world to come.

Engineering audacity on a 230-foot canvas

The Peacemaker’s silhouette defied convention. Its six Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major radial engines sat in pusher configuration, with propellers at the back of the wings. That kept drag down and improved high-altitude performance, but it also made maintenance a bear. Each engine had 56 spark plugs—336 in total—turning routine service into a long, finger-numbing ritual for ground crews.

Beginning with the B-36D variant, four General Electric J47 jet engines were added in pods under the wings. Pilots could light the jets for takeoff and high-speed dash, inspiring a nickname that stuck: six turning, four burning. The hybrid powerplant gave the huge bomber surprising agility when it mattered most, even as it cruised serenely at altitudes that challenged early interceptors.

Inside, the aircraft was a pressurized, tube-connected world of its own. Forward and aft compartments were linked by a narrow tunnel that crew members traversed on a wheeled trolley. Long missions demanded humane touches—bunks, a galley, and room to stretch—because a Peacemaker sortie could last well over 30 hours and sometimes approach 40. Crews typically numbered more than a dozen, with roles spanning pilots, navigators, bombardiers, radio operators, and gunners.

For defense, early B-36s bristled with remotely operated turrets mounting up to sixteen 20 mm cannons. Later aircraft shed much of that armament in favor of performance and range as tactics and threats evolved. What didn’t change was the cavernous bomb bay: the B-36 could carry up to 86,000 pounds of ordnance, including early-generation nuclear weapons that required space as much as secrecy.

A Cold War sentinel with ocean-spanning reach

Strategic Air Command relied on the B-36 as the United States’ first truly intercontinental nuclear bomber. It could launch from the continental U.S., fly over the Arctic or across the Atlantic, and return without refueling—an essential capability before aerial tankers and global basing were reliable. The aircraft’s altitude and endurance meant fewer compromises: crews could take long, arcing routes to avoid weather or simulated defenses during training and exercises.

The Peacemaker served not just as a bomber but as a reconnaissance platform. In RB-36 configurations, it carried cameras and mapping gear that turned remote stretches of the globe into high-resolution film, feeding planners vital terrain and target intelligence. This dual identity—deterrent and data-gatherer—made it a quiet but central character in the early playbook of the Cold War.

Its presence also enforced a new strategic reality. Long before missile silos dotted the Plains, the B-36 gave adversaries a deterrent to ponder: a fleet of aircraft able to reach almost anywhere on Earth from North American bases. That reach shaped diplomatic calculations as much as military planning, buying time for jets like the B-52 Stratofortress and the first generation of intercontinental ballistic missiles to take the stage.

When a bomber carried a reactor

Even for an aircraft built on ambition, one of the B-36’s most startling chapters came with the NB-36H. As part of the Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion program in the 1950s, engineers installed a functioning nuclear reactor inside a specially modified Peacemaker to study shielding and crew safety. The reactor never powered the airplane; the conventional engines did all the flying while instruments measured radiation and barriers were tested in flight.

The concept was radical and short-lived, but the lessons were real. The NB-36H flights proved that effective shielding could protect crews, even if the operational logic of nuclear-powered flight never added up. In that way, the Peacemaker again acted as a bridge—this time between an idea too bold for its era and the pragmatic limits of technology and risk.

Limits, lessons, and a lasting legacy

No airplane that big and complex gets everything right the first time. Early B-36s suffered engine reliability issues, especially in harsh weather and at the punishing altitudes where they were meant to excel. Convair and the Air Force worked through the problems, improving systems and procedures, but the jet age was closing fast. By the late 1950s, the more efficient, faster B-52 was ready to take over the mission the Peacemaker had kept alive.

Yet the B-36 left behind more than scrap and statistics. It proved that global reach could be a routine expectation rather than a heroic exception. It forced advances in high-altitude navigation, crew endurance, and systems integration on a scale never attempted before. And it showed, in metal and rivets, that deterrence in the nuclear age would be as much about credibility and persistence as about speed.

A handful of Peacemakers survive, their sheer size still startling in the desert light of Arizona and the hangars of Ohio. Visitors at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton and the Pima Air & Space Museum in Tucson can stand beneath those towering wings and trace the arc of aviation history with their eyes. The aircraft that once made other giants look small now serves as a landmark—of engineering confidence and strategic anxiety, of the moment when propellers and jets briefly shared the same sky.