He could not outrun a mountain. As Mount St. Helens ripped itself open on a quiet Sunday morning in 1980, photographer Robert Landsburg kept shooting, then did the only thing he could think to do with the seconds he had left: he protected the pictures.

When the mountain woke

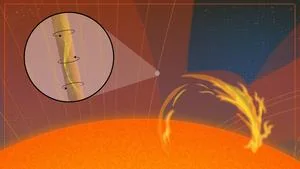

On May 18, 1980, at 8:32 a.m., a magnitude 5.1 earthquake destabilized the swollen north flank of Mount St. Helens. The bulging slope collapsed in an instant, releasing the largest landslide in recorded history and uncorking a lateral blast that flattened forests like matchsticks.

The force was staggering. The sideways explosion raced outward at speeds estimated near 300 miles per hour, scouring 230 square miles of timber and sending a column of ash to roughly 80,000 feet. Fifty-seven people would die, and ash would fall across much of the United States in the days that followed.

For weeks, geologists and journalists had watched the volcano stir—swarms of earthquakes, plumes of steam, a bulge growing at the summit like a bruise under the snow. What few anticipated was the direction and ferocity of the blast. The hazard zones on maps did not imagine a sideways explosion that would behave more like a supersonic avalanche than a classic vertical eruption.

The photographer who stayed

Robert Landsburg, a 48-year-old photographer from Portland, had been making regular trips to the mountain to document its changes. He was one of many drawn by the rumbling volcano—scientists with seismographs and field notebooks, locals keeping wary eyes on the skyline, and a handful of photographers determined to capture a once-in-a-generation event.

That morning, Landsburg positioned himself within a few miles of the summit, a distance that might have been safe in a typical, upward-blasting eruption. When the slope collapsed and the lateral blast tore northward, the calculus changed. As the ash cloud roared toward him, he moved toward his car, still shooting. Then, realizing escape was impossible, he rewound his film, sealed the roll, stowed the camera in his backpack, and lay on top of it to shield it from the superheated onrush.

He was found 17 days later, buried under ash, his backpack beneath him. The film survived. Developed after recovery, his final frames offered a sequence of the approaching cloud and the volcano’s first violent moments—images that researchers would later use to refine the timeline and dynamics of the blast.

“Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!” — USGS geologist David A. Johnston, radioing moments after the mountain broke apart

Johnston’s transmission, crackling across radios from a ridge miles away, has come to symbolize the shock of that morning. Landsburg’s pictures are the still counterpart: a deliberate record wrested from chaos by someone who kept working even as the disaster bore down.

What his last frames gave science—and us

It is tempting to tell Landsburg’s story as a myth of singular heroism. The truth is both plainer and, in its way, more profound. He did not set out to die for pictures. He put himself where many thought was safe enough to work, and when the mountain proved otherwise, he used his remaining time to do his job and make sure the work would endure.

Those frames mattered. Combined with seismic records, weather data, and other photographs and films, they helped scientists reconstruct the first minutes of the eruption and calibrate the behavior of the lateral blast. In a field where seconds count and vantage point can skew understanding, a clear, timestamped sequence from close range is rare and valuable.

They also carry a different sort of weight: a reminder of what pyroclastic density currents really are. They are not clouds you can outrun. They are ground-hugging torrents of ash, gas, and shattered rock moving faster than a car on a logging road, hot enough—often over 400°C—to incinerate and suffocate in a heartbeat. Disaster movies get this wrong. Landsburg’s film, and the devastation carved into the landscape, do not.

Hindsight asks whether he should have been there at all. The weeks before May 18 brought roadblocks, warnings, and lively debates about access and risk. But the mountain was also a magnet for documentation because the world learns from what it can see. The scientific understanding that followed—the way hazard maps are drawn, the way emergency officials talk about lateral blasts, the public’s sense of what an active volcano can do—owes much to the thorough record assembled by many people who accepted real risk, and sometimes paid for it.

Presence of mind is its own quiet form of courage; it turns the last few seconds into a legacy measured in knowledge, not spectacle.

Four decades on, the tools are different. Drones, remote cameras, satellite constellations, automated ash sensors—these can keep eyes on a peak without placing a person in the blast zone. Agencies rehearse exclusion zones and evacuation plans for scenarios that specifically include lateral blasts. Journalists and scientists alike are more explicit about risk calculus on dangerous assignments.

Yet the tension remains. Curiosity pulls us toward the front line; prudence pulls back. Landsburg’s story offers a way to hold both truths. It does not ask for an altar or a cautionary wag of the finger. It asks us to acknowledge the unglamorous professionalism of someone who prepared, observed, adapted when the plan failed, and, in the end, treated information as something worth saving.

- Volcanoes do not always erupt skyward; lateral blasts can be faster and deadlier than expected. Hazard maps and plans must reflect that reality.

- Documentation saves lives later. Today’s remote sensing and strict safety protocols exist so we can keep learning without repeating the same human cost.